The Trial: Photography and AI

© 2025 Robert Hirsch and Edward Bateman

The right understanding of any matter and a misunderstanding of the same matter do not wholly exclude each other.

— Franz Kafka, The Trial (1914/1925)

Perhaps Kafka best evokes where we stand with art and AI. Not in a battle between truth and falsehood, originality and imitation, but in a strange new space where understanding and misunderstanding coexist. With it comes a new way of seeing, not through the camera lens, but through Kafka’s eye: a gaze that observes, classifies, judges, but never offers explanations. It is a space where machines echo our vision, yet never quite see. It is a place where the image is no longer just a record of light, but a remix of perception, culture, and code. Conceivably, it is not the end of art, but its next great riddle. It is the space where photographic representation no longer holds primacy, but rather is supplanted by algorithmic interpretation and predictive calculation. The result is a profound shift in how we understand evidence, identity, and humanity itself.

Charge 1: Impersonation of Reality and Sedition Against Photographic Truth

The accused stands charged with simulating reality to such a degree that the original can no longer be trusted, and with overthrowing indexicality – the sacred trust between image and referent. What was once a mirror of the world is now a hall of mirrors, each reflection detached from the light it claims to echo. In doing so, the accused undermines photography’s historical role as evidence, as memory, and as witness.

One of photography’s foundational properties has been its indexicality: the certainty that a photograph bears a physical trace of reality, rooted in light passing through a lens onto film or sensor. From the beginning, this indexical connection promised to ground memory, truth, and meaning. Yet photography has never been a purely neutral record. Framing, cropping, hand-coloring, retouching, and staged elements, such as poses, props, costumes, have always enabled the construction of alternate or selective realities. In short, all photographs have always been constructions.

The advent of the airbrush, popularized after the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, marked a turning point in photographic manipulation. It allowed tonal adjustments that mimicked the look of unaltered camera images, enabling the creation of idealized glamour in Hollywood and politically motivated image revisions under authoritarian regimes like Joseph Stalin’s. The term “airbrushing” entered our cultural vocabulary as shorthand for concealing or altering inconvenient truths.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, expensive digital retouching systems like the Scitex Response 300 ushered in a new era of image manipulation. Used by elite publishers and advertisers, these room-sized machines could reshape images, further distancing photographs from reality, even as they remained grounded in a physical referent.

But then, like a thief in the night, came Photoshop. The release of Adobe Photoshop 1.0 (1990) marked a pivotal moment, breaking photography’s traditional indexicality. But more importantly, its wide-spread adoption allowed anything that could be imagined to be created with photographic precision. The rise of AI echoes the past protests of analogue photographers who believed digital imaging was murdering photography.

Artificial Intelligence breaks even that final tether as its images are no longer bound to a moment, a place, or light itself. They are simulations, constructed from vast datasets of existing images, usually without consent, physical interaction, or traceable authorship. This shift has sparked a debate: Can these images, which bypass the camera entirely, still be considered photographs? Critics argue they are derivative, ethically opaque, and devoid of the authenticity that once made photography a witness to the real.

Such skepticism mirrors the initial rejection of photography itself as art in the nineteenth century: a suspicion of mechanical vision replacing human expression. But today’s anxiety is deeper. AI does not just extend photography’s manipulative potential; it displaces its foundation. The bond between referent and representation is severed.

In this brave new hall of mirrors, it is no longer enough to ask what a photograph shows. We must ask: What is its origin? What is its objective? And above all: Can it still be trusted?

Charge 2: Refusal to Explain Itself

The accused refuses transparency. Its inner workings remain a black box. Its logic is inaccessible even to its creators. Kafka’s court gave no reasons—neither does the algorithm.

The accused generates images, but withholds its reasoning so that all we see is the result. AI unmoors photography from its link to the light bouncing off a subject. Its process is synthetic, not optical; predictive, not experiential. Like Kafka’s court, it renders judgments without disclosing criteria. We see the sentence, but not the trial.

In traditional photography, even manipulated images retained some indexical tether to the real. With AI, that tether is cut. What remains is inference wrapped in style: a simulation of evidence with no scene, no shutter, no witness. We confront portraits of people who never lived, moments that never happened. And yet they feel familiar, even intimate. The danger is not just in deception, but in comfort: these images ask nothing of us. They do not challenge; they seduce, laying bare our mindless inclinations.

Deepfakes and AI-generated photojournalism now blur the boundary between visual documentation and persuasive fiction. A fabricated protester in a war zone, a smiling leader at a non-existent peace summit, become history revised. Often such images circulate faster than truth. When plausibility replaces provenance, and aesthetics stand in for accountability, the photograph no longer functions as a witness, but as a mask. If the machine cannot explain itself, we must question our own role: are we still the interpreters of images or just the consumers of hallucinations?

Charge 3: Trespassing in the Artist’s Studio

The accused has infiltrated the space of solitude and reflection, where ideas are meant to gestate. Now the artist’s studio is shared with a non-sentient assistant who never sleeps and always answers.

This question raises another dilemma: How much active or passive mental and physical engagement is necessary for the results to be considered a creative act? The yet unknown possibility is this: Can AI ever master the creative principles that transform ideation or a feeling into an aesthetic experience? Or will it remain a second-rate mind; one lacking independent thought, and blind to questions of authorship, authenticity, bias, environmental damage, and labor? If so, how might AI challenge the workshop sanctuary of the artists’ studio? Could AI devour this preserve up by achieving a form of phenomenological consciousness with its own personalities and creative desires that compete with humans? One way or another, AI is already transformational. Thus, the future of creativity lies not in the exclusion of AI, but in its integration into the evolving narrative of what it means to be human.

Unlike the human brain, machines are not confined by genetically evolved rules and can escape the trodden paths of thinking. AI can experiment with unusual combinations of data that we find both unfamiliar and remarkable. AI systems might soon be thought of as world-class oracles, capable of answering questions on any topic more accurately than human experts. However, being able to process massive amounts of data is not the same as being creative, which is the capacity to take such data and finding novel way of using it. Photography demands effort and practice to push through uncertainty and become an expert who can merge subjectively and technology to generate a unique experience.

Charge 4: Subversion of Authorship

The accused is alleged to have committed theft of the collective legacy of the human creative heritage. AI generates images without body, context, or experience, thus raising questions of originality, ownership, and exploitation. When the tool “creates,” who signs the work?

This charge can seem odd considering that it has been over 100 years since Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) and the first of his Readymades like the Bicycle Wheel (1913). While unquestionably canonical works, their seeming lack of “originality” continues to challenge some. This was the beginning of Conceptualism and other twentieth century art movements, which shifted the focus from object to idea. There is something strikingly similar to AI prompts in the work of Sol LeWitt who wrote: The idea becomes a machine that makes the art. This distinction, has risen anew with AI and opens the possibility of making art without artists. This changes our relationship with art as being a reflection of our humanity.

This technological rupture raises existential questions about authorship, and its attendant trust and meaning in a world flooded with convincing illusions. As with every disruptive shift, from the daguerreotype to digital photography, some cling to older methods while others explore new creative frontiers. But the stakes are higher now: not just aesthetic, but epistemological.

Since AI systems reflect their training data, which devours everything it can on the internet without permission, along with the biases of their programmers we must ask: Is AI a tool of exploitation or inclusion? The program’s mimicry challenges long-held concepts of authorship, authenticity, copyright, and cultural appropriation in AI-generated works, leading some to call for guardrails. This brings to the fore: Is it the fault of the tool or the user when works go off the rails, such as producing disinformation (a favorite tool of authoritarian regimes), whose intent is to deceive that can cause harm? On the other hand, could this be part of a longer arc akin to how photography itself was once dismissed as soullessly mechanical?

Charge 5: Mistaking the Tools for the Metamorphosis

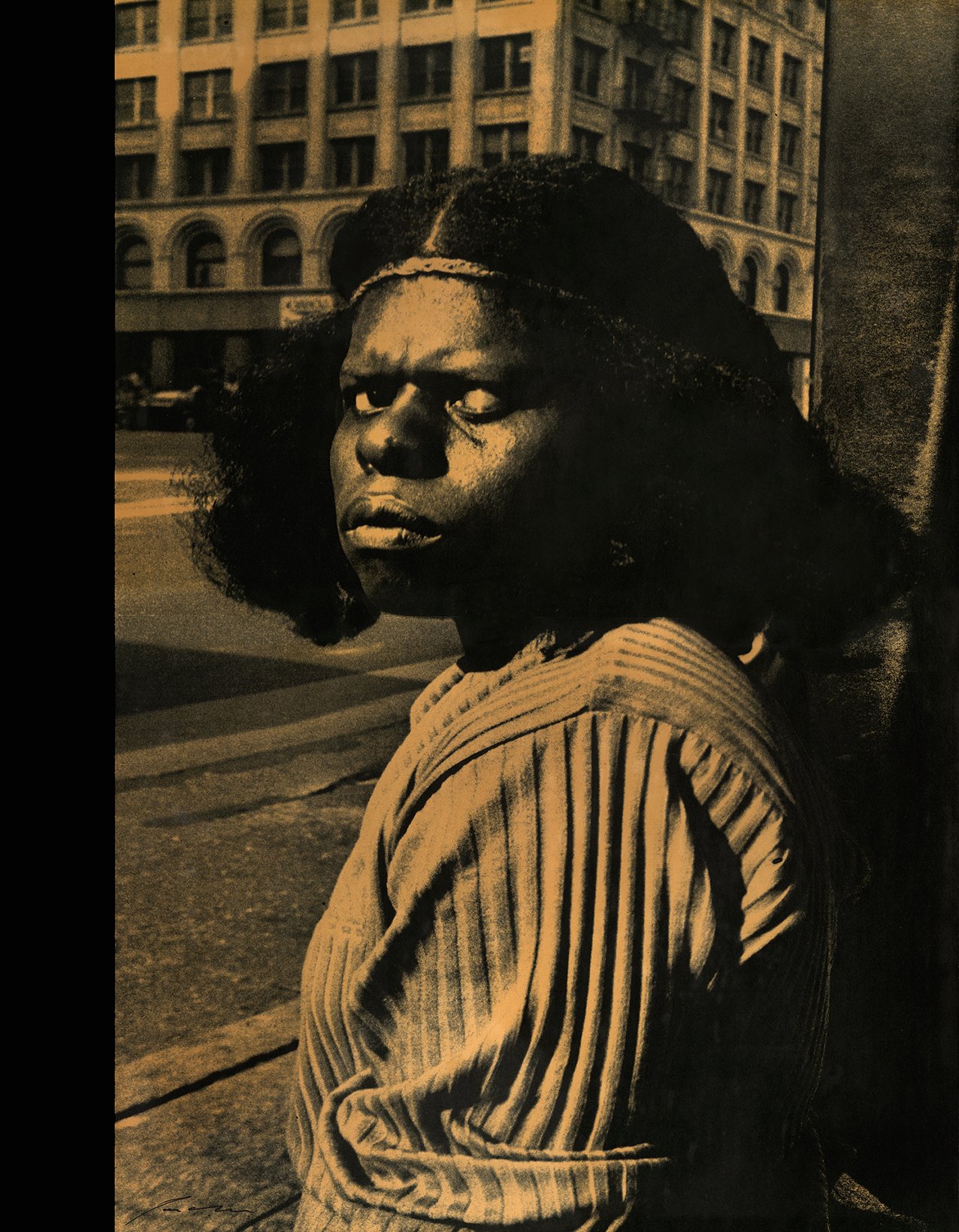

The accused (technological progress) is celebrated for transforming photography—yet the most meaningful innovation has not been in form, but in authorship. Over the past 25 years, it is not aesthetics that have radically shifted, but access. The on-going democratization of imagemaking has reshaped whose images are shown in museums and whose narratives are prioritized. The revolution came not through code, but through selected representation that has favored certain groups of people over other groups of people. AI now enters this space not just as a new tool, but as a new filter—one that risks flattening this diversity into predictive uniformity.

While AI promises radical shifts in imagemaking, the most visible transformation in photography over the past 25 years has been social, not its digital revolution. The medium has become more inclusive; expanding who is being represented and whose gaze is now spotlighted. But curatorial institutions, long slow to embrace this change, have recently made equity their dominant lens, sometimes to the exclusion of other values. Visual experimentation and aesthetic innovation have taken a backseat to representational correction, as if the who of the image now matters more than the how. This is not a rejection of inclusion, on the contrary, it is a call to hold space for both: to recognize that formal innovation and expanded authorship are not competing goals, but historically intertwined. Yet today, the visual language of many exhibitions remains strikingly conservative. Is this because nothing has changed – or because curators, eager to be seen as socially attuned, have chosen to downplay the radical potential of photography itself?

Charge 6: The Theft and Destruction of (our shared) Cultural Heritage

Making a photograph is a political act. It is a vote for something you feel is important, something you believe is worth remembering. It is an exercise of one’s personal autonomy and an expression of independence of mind. This action is not mimicry; it is a temporal state made visible, a reckoning framed by light. AI may now be part of this process – extending what we see, suggesting what we might not – but it does not wait for light, nor does it feel the weight of intention or memory. It is a reckoning, a resistance, a flash of light saying: I was here. AI may offer speed, scale, even spectacle, but it does not hope, grieve, or wish as we do. Most importantly AI cannot differentiate between what is true and what is false. This plays into our current post-fact environment in which emotions and personal beliefs outweigh objective facts in shaping public opinion. In this atmosphere, truth becomes relative, and verifiable evidence loses its authority in favor of narratives that align with emotional or ideological preferences.

Every photograph we see of any subject becomes part of our definition for that thing, with the power to even over-write individual memories. In terms of history, the most persuasive evidence is visual. As French historian and philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman wrote, “To show, to try to render visible, is to resist.” Then let us show. Let us resist. Let us choose what matters. We press the shutter, real or virtual, and say: This is the world we want to remember. This is a responsibility that should be taken very seriously. Once an image becomes public, there is no taking it back. Even with warnings, it will be remembered, changing people’s perception to align with what the fake photograph depicts, thus making reality completely malleable.

When AI generated images about Holocaust appear on social media, posing as genuine, they encourage viewers to conflate historical fact with fiction. Such fabrications, both images and text, which many people indifferently accept as true, present serious ethical risks by casting doubt on the authentic visual testimonies of the Holocaust, exploiting the trauma of victims for viral or manipulative purposes, and enabling Holocaust denialism. Another problem is that some viewers do not seem to care if the images are fake, making them more susceptible to conspiracy theories and disinformation. Such illusionary historical documentation raises serious moral concerns that mirror Kafka’s existential dread about the erasure or rewriting of reality. The Auschwitz Museum publicly condemned these AI images, attempting to preserve the veracity of original Holocaust images that served as evidence in criminal cases like the Nuremberg Trials.

Additionally, Grok, the artificial intelligence chatbot owned by Elon Musk, responded to multiple X users on July 8, 2025 with mendacious antisemitic conspiracies, after an update intended to make the tool “less politically correct,” and eventually began referring to itself as “MechaHitler.”

The Trial wrestles with the absurdity of human existence and our struggle to find meaning in a world governed by forces beyond our comprehension. Kafka’s court is indifferent: receiving, dismissing, watching, but unmoved. Perhaps AI, too, is such a court: neither cruel nor kind, only procedural. It renders images, not judgments. But art does not emerge from silence. It demands a witness. So if we are now all caught in this incomprehensible trial, trapped between invention and imitation, let us not wait for verdicts. Let us create the evidence.

Awaiting a Decision

The court wants nothing from you. It receives you when you come and it dismisses you when you go.

Speculating on the future of artificial intelligence (AI) is like trying to imagine the Industrial Revolution from the mindset of an eighteenth-century miniature painter. We build the future from our actions. However, our apathy, fears, greed, and malice can often overshadow our dreams. We may be certain of our innocence in this trial or the justness of our cause. We may even be foolish enough to think we are the prosecutor rather than the accused. We may deeply believe in the power of the photographic act. But this is Kafka; and it is human nature that is on trial.

Glossary

A neural network is a core technology behind AI systems like OpenAI’s ChatGPT. It’s a mathematical model inspired by the human brain, designed to recognize patterns and learn from large amounts of data. For example, by analyzing thousands of dog photographs, it can learn to identify what makes a dog look like a dog.

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) describes a machine that would be capable of doing any intellectual task the human brain can do.

Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) refers to a theoretical AI that would far surpass human intelligence in nearly every field, including creativity, emotional insight, and scientific reasoning.

Endnotes

1 Franz Kafka, The Trial, Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir, New York: Schocken Books, 1998, 226.

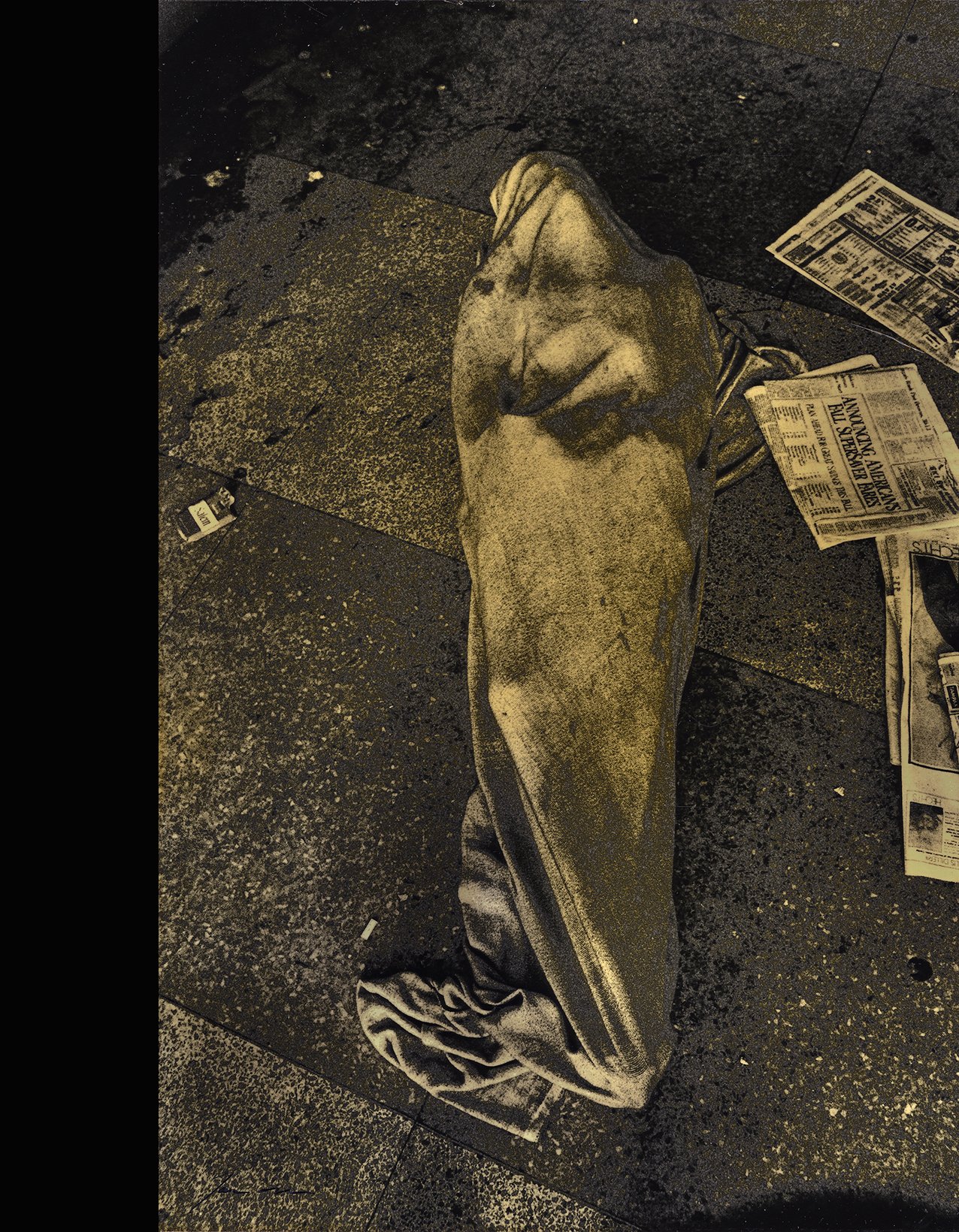

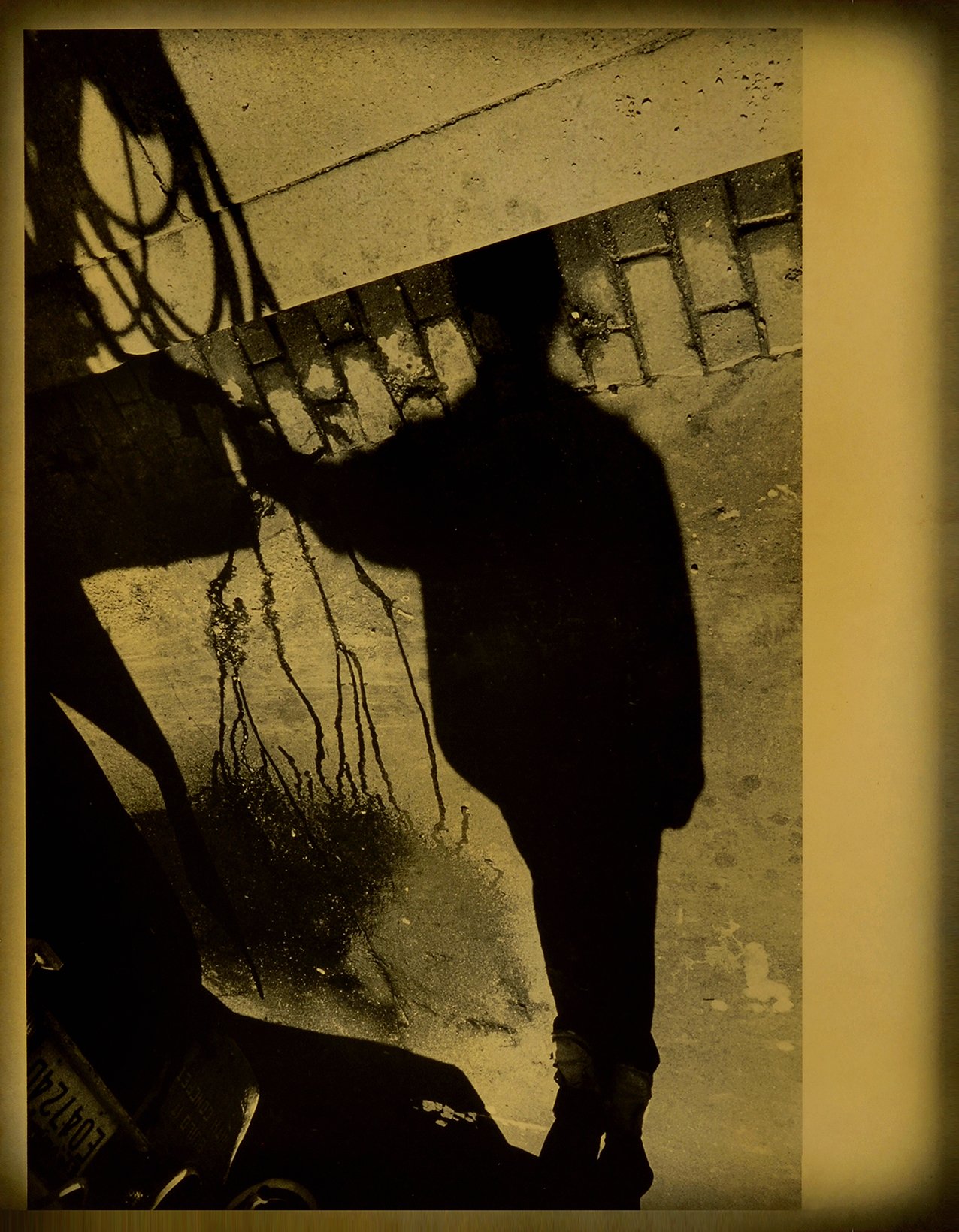

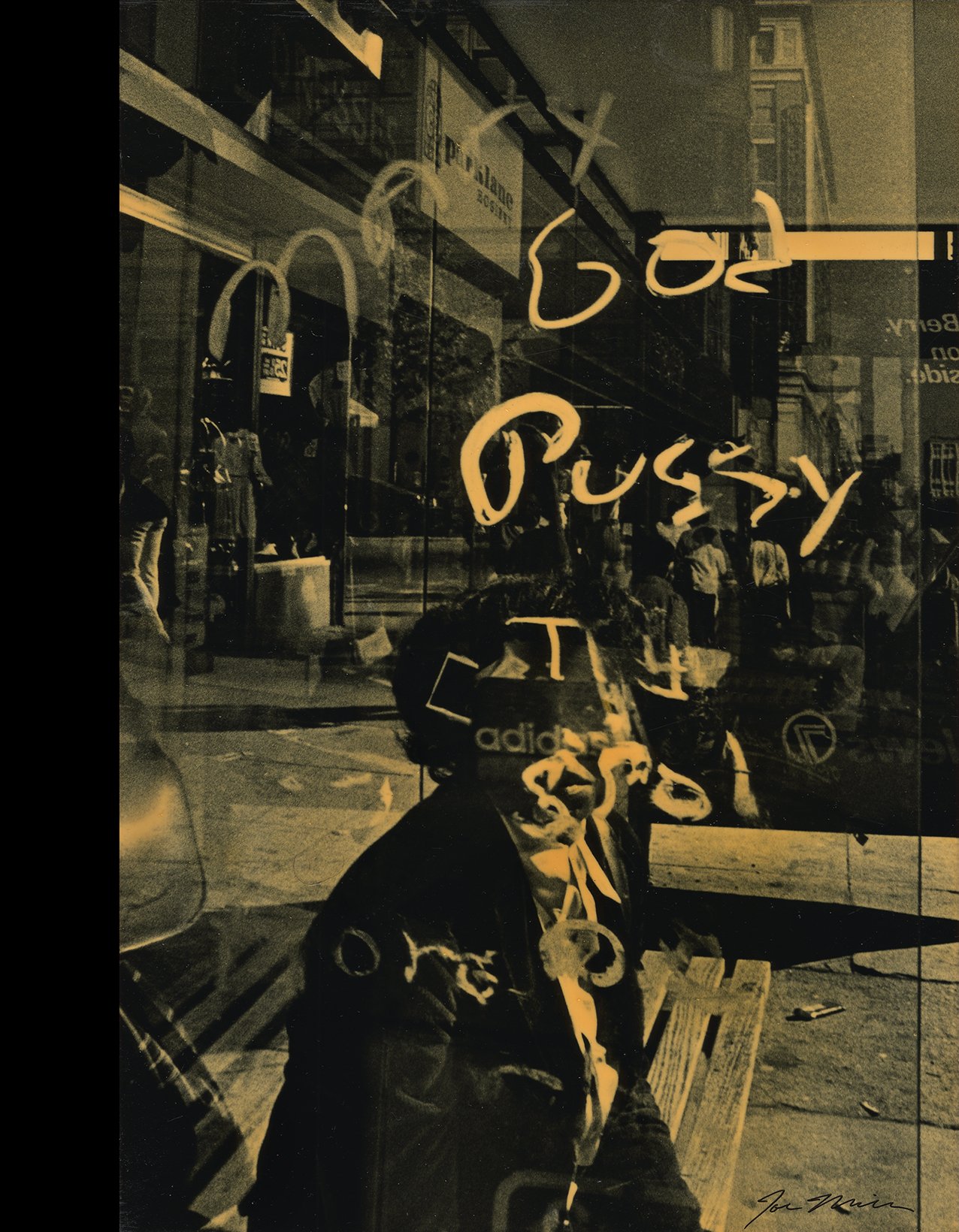

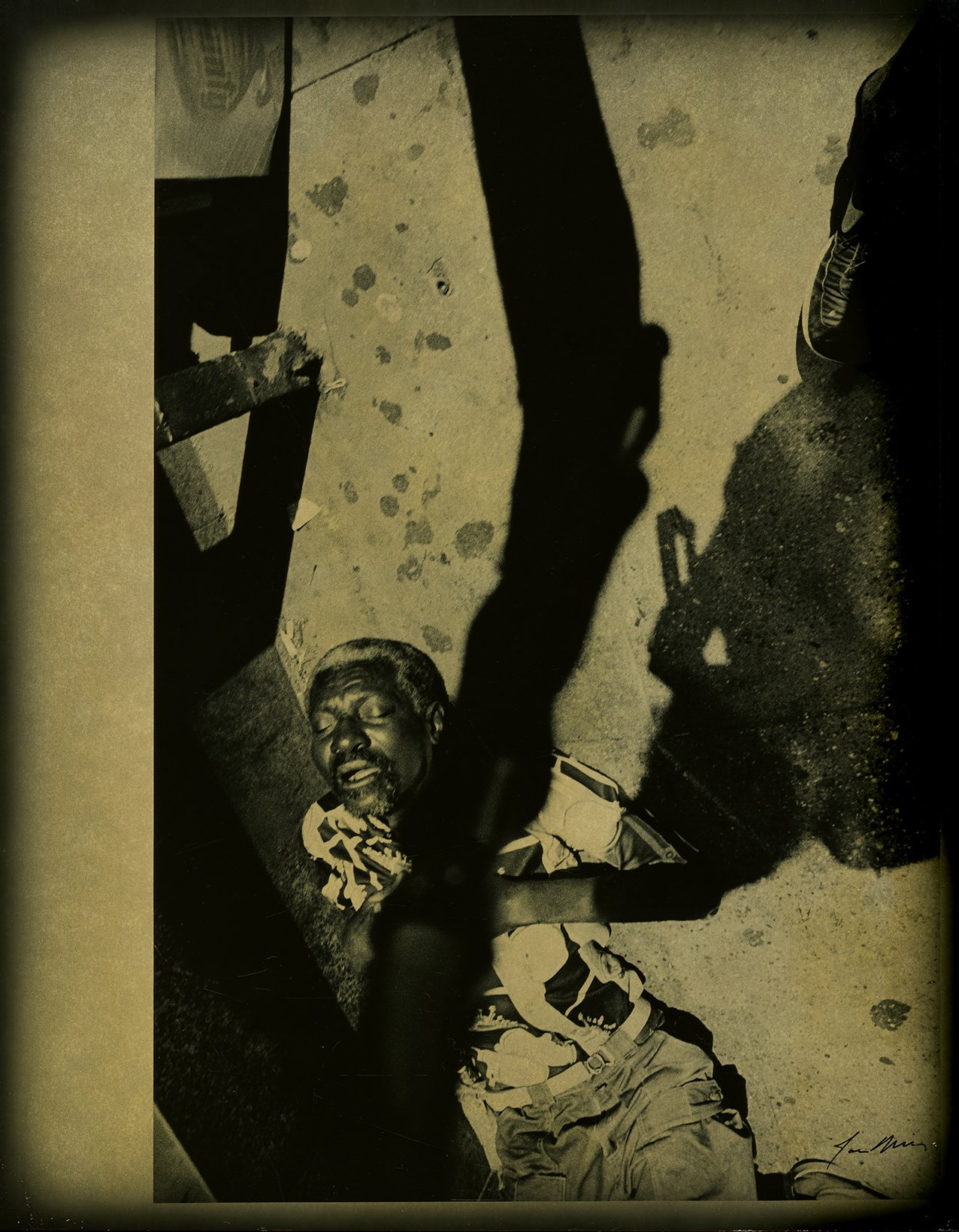

2 Note: All images presented here, with the exception of one, have been modified in various ways by AI. More about this will be discussed in our next essay.

3 See: David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia, New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt (US), 1997.

4 “Readymade” refers to everyday, mass-produced objects that Duchamp selected and presented as art, often with little to no modification, which played a vital role in the development of conceptual art.

5 Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum 5, no. 10 (June 1967): 80.

6 Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz. Translated by Shane B. Lillis, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

7 See: Jerusalem Post Staff, “Dangerous distortion, Auschwitz Museum calls out AI-generated images of Holocaust victims,” June 1, 2025, www.jpost.com/international/article-856178

8 Arno Rosenfeld, “Calling itself ‘MechaHitler,’ Elon Musk’s AI tool spreads antisemitic conspiracies,” Forward, July 8, 2025, https://forward.com/fast-forward/753703/grok-cindy-steinberg-elon-musk-antisemitism-ai-chatbot/ & Kate Conger, “Elon Musk’s Grok Chatbot Shares Antisemitic Posts on X,” The New York Times, July 8, 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/07/08/technology/grok-antisemitism-ai-x.html?searchResultPosition=2

9 This AI generated Holocaust image, and others like it, have been posted on Facebook by a group that identifies itself as 90’s History- www.facebook.com/groups/1120040369102305?ref=profile_plus_visit_group

10 Franz. Kafka, The Trial, p. 278.

11 For details see: Karen Weise and Cade Metz, “At Amazon’s Biggest Data Center, Everything Is Supersized for A.I.,” The New York Times, June 24, 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/06/24/technology/amazon-ai-data-centers.html?emc=edit_nn_20250625&instance_id=157224&nl=the-morning®i_id=124728665&segment_id=200612&user_id=019b62469e7b1b8a3119a3a877622d89

Image Captions

Figure 4.1 Orson Welles. The Trial, 1962. Film still. Under “open arrest,” Josef K. (played by Anthony Perkins) is trapped in a surreal and labyrinthine system where the sentence precedes the crime, and the prisoner and the warden are one and the same. He runs not from guilt, but from the absence of meaning. Orson Welles called The Trial his best film. With the ascent of technocratic bureaucracy, Kafka’s reputation as an advocate for humanity against monolithic forces of conformity and repression made him an emblem of individuality in the face of the machine.

Figure 4.2 Arnold Genthe. Greta Garbo, 1925. 9-1/16 x 7 1/8 inches. Gelatin silver print. Cleveland Museum of Art. The airbrush gave artists, illustrators, and photographers the ability to manipulate surfaces with unprecedented subtlety, allowing reality to be altered into idealized and stylized forms. The airbrush became essential in commercial art, photographic retouching, Hollywood glamour as well in pin-up art and pulp fiction covers. Genthe photographed many theater and film personalities, including a young Swedish film actress named Greta Garbo who had just arrived in New York. Genthe’s retouched photographs are credited with boosting Garbo’s career.

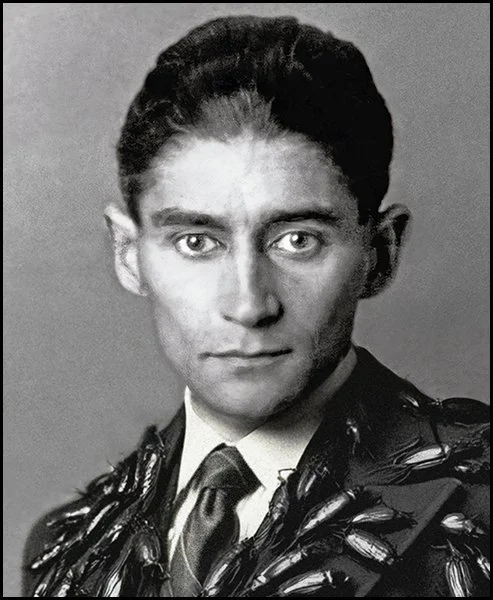

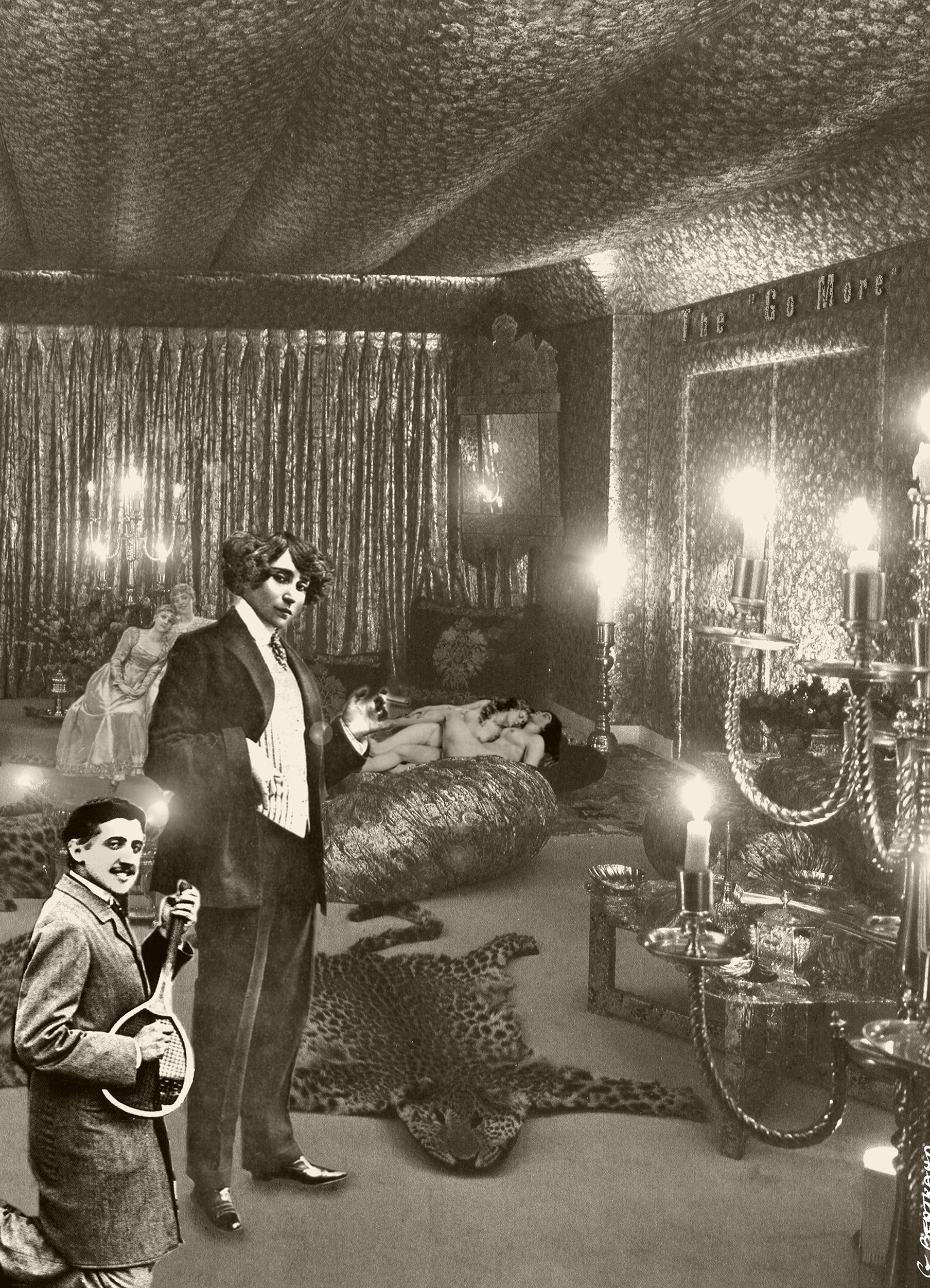

Figure 4.3 Unknown maker. Franz Kafka, circa 1923. Gelatin silver print. Klaus Wagenbach Archive, Berlin. Franz Kafka’s Trial reflects a world where truth is obscured, authority is arbitrary, and the self is at constant at risk of erasure. Kafkaesque situations include: Rules exist, but no one understands them; You are judged, but you don’t know why; a system that speaks in circular riddles, answers with silence, and punishes you for the rules you didn’t know existed.

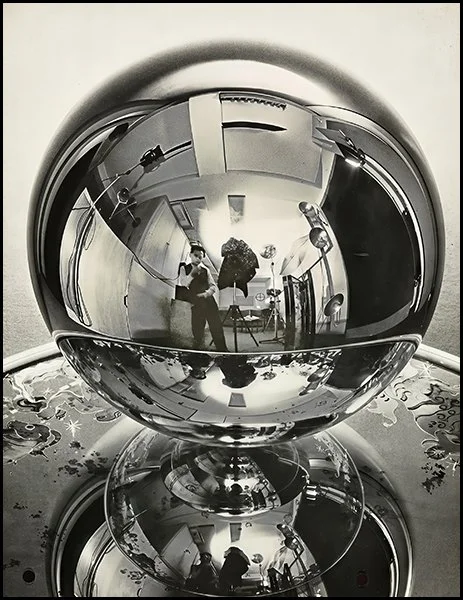

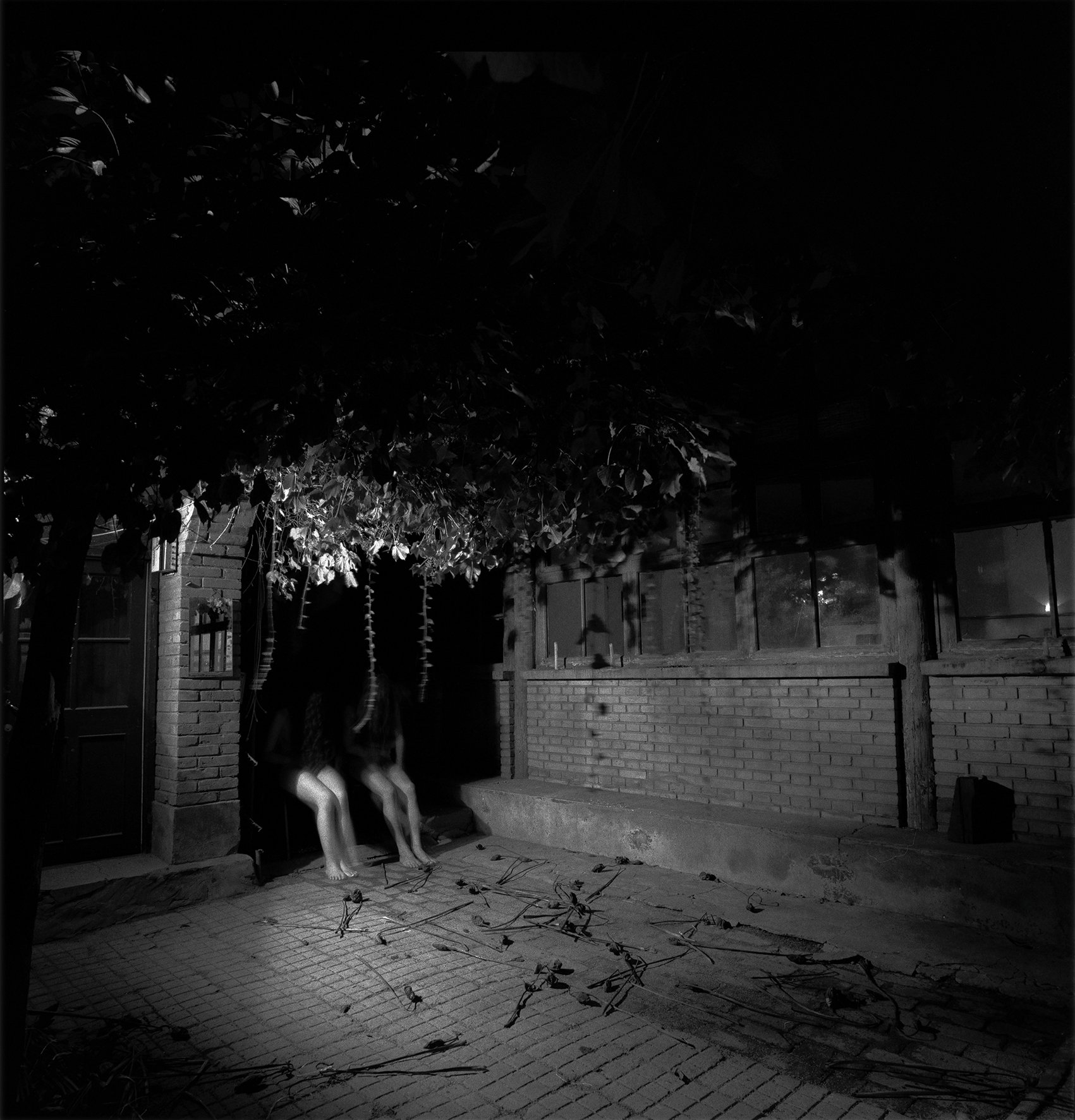

Figure 4.4 Man Ray. Laboratory of the Future, 1935. 9 1/16 × 7 inches. Gelatin silver print. © 2025 Man Ray Trust. Man Ray’s studio was a space where experimentation was both a method and a philosophy. In this mirrored self-portrait, the studio becomes a site of distortion and recursion—artist, tools, and environment reflected endlessly into themselves. Today, the solitude of this space is breached, not by muses or models, but by algorithms that generate without feeling, and assist without rest. What happens when the artist’s assistant never blinks, never doubts, and always produces?

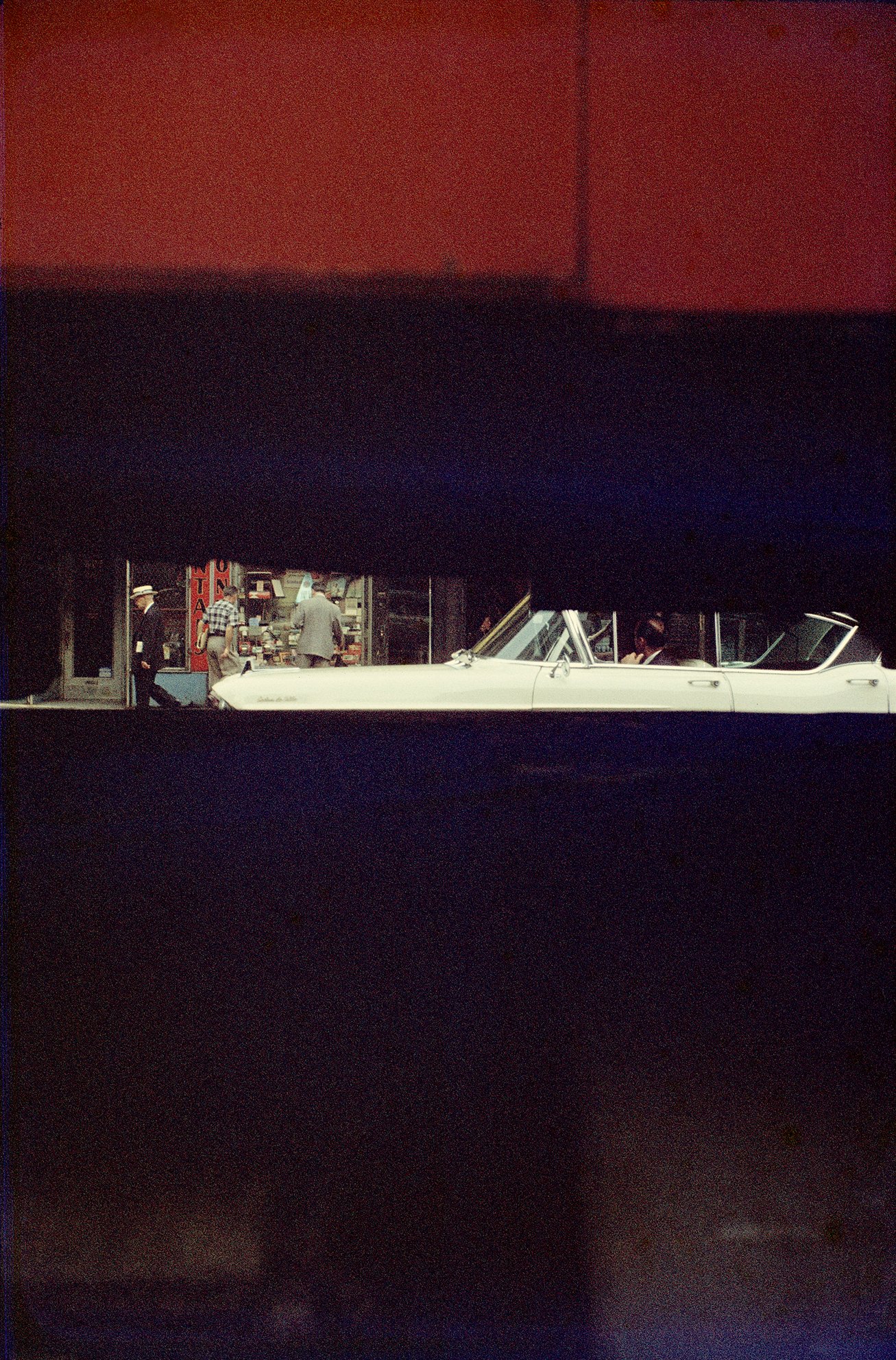

Figure 4.5 Alfred Stieglitz. Fountain, 1917. Photo offset. Stieglitz made this photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain in his 291 art gallery, after the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit, with entry tag visible. The backdrop is The Warriors by Marsden Hartley. The image was published in the Dada magazine The Blind Man in 1917. The original work is lost as is Stieglitz’s negative.

Figure 4.6 Kate Crawford. & Trevor Paglen. Training Humans, 2019. Variable dimensions. Photo-based and video installation. Training Humans explores the collections of photographs used by scientists to train artificial intelligence (AI) systems in how to “see” through pre-categorized images, raising questions of bias and classification. AI image generators start with random noise and then gradually remove that noise, guided by what it has learned about images and the prompt text: a process inherently alien to human experience.

Figure 4.7 JR. Au Panthèon, 2014. Installation. Panthèon, Paris. JR’s Inside Out Project makes photography an act of social engagement through portraits made of everyday people, like those gathered through his traveling Photo Booth truck, and displaying them in public spaces. With over 2,500 group actions across 152 countries, his work has achieved a populist appeal while critical response has been mixed. Often described as aesthetically conventional and politically soft, his work is frequently accused of creating the feeling of activism or resistance without structural critique. In other words, it’s socially comforting, not socially challenging. While JR positions himself as a populist working outside the museum system, his projects have been embraced by elite institutions like the Louvre and major art biennials.

Figure 4.8 ©90’s History (Facebook group). Alice Herz-Sommer, Theresienstadt, 2025 Variable dimensions.Digital file. This AI generated image falsely claims to show Alice Herz-Sommer playing the piano at the Nazi SS show camp of Theresienstadt, which in fact was a waystation to the extermination camps. The Auschwitz Museum states the AI-generated materials posted on 90’s History Facebook page have been fabricated from information and photographs from its website. This triggers the problem of what happens when people decide to believe in fake news instead of the authentic history and journalism.

Figure 4.9 A. J. Mask. Amazon Data Center, New Carlisle, Indiana, 2025. Variable dimensions. Digital file. A year ago, this 1,200-acre stretch of farmland outside New Carlisle, Indiana was an empty cornfield. Now, seven Amazon data centers rise up from the rich soil, each larger than a football stadium. These silos of AI logic echo Kafka’s castle: unapproachable, enigmatic, and all-powerful. The facility will consume 2.2 gigawatts of electricity, which is enough to power a million homes. Each year, it will use millions of gallons of water to keep the chips from overheating. And it was built with the aim to create an A.I. system that matches the human brain. Amazon plans to build 23 more. The colors of this image have been altered, along with an AI generated sky, to become more Kafkaesque.