Stan Douglas is an established artist who has been represented at Documenta, the Venice Biennale and has had exhibitions at the Serpentine Gallery in London, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, The Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid as well as at the DIA Center of the Arts in New York. Most of his video installations employ computers and multiple projectors with varying film or video length to overlap dialogue and action resulting in a wide variation of occurrence within a given storyline or situation. This multiplicity of perspective is central to Douglas’s work as he is constantly revisiting, recreating and uncovering implied and universal truths in a specific circumstance. Many of his videos last for several hours and provoke viewers to decide for themselves when they have comprehended the meaning or have become satisfied with a complete story which, as Douglas’ work reminds us, can never be fully complete and continues to evolve in waves of repercussion and new interpretation.

Douglas’s videos dispense with traditional storytelling in an effort to

ask viewers to consider the wider complexities of cause and effect, action and reaction, thesis and antithesis. Douglas draws upon and references sources as diverse as 1950’s American interior design, Akira Kurosawa’s, Rashomon, Sigmund Freud, Alfred Hitchcock, Samuel Becket and The Grimm Brother’s

Fairy Tales and then grounds them within a new context and composition that ignites new meanings. “The structure is a bit complicated. But then, the genre of investigating events is complicated. Plus, stories are complicated by their very nature. I am not interested in the simplicity that is offered in mass storytelling.

The kind of storytelling I’m after is almost inconceivable compared to Hollywood films where everything is packaged in digestible servings. That type of filmmaking is decided by commerce. Commerce determines the form. I’m using other conditions – permissible by the false autonomy of the art world.” In Klatsassin, Douglas creates a story around the killings that occurred in British Columbia in 1864 when gold miners were murdered, reportedly by the Tsîlhqot’in Chief, Klatsassin, and other members of his tribe. Klatsassin means “we do not know his name” in the Tsîlhqot’in language and the storyline spreads out from this central mystery adding more uncertainty and re-evaluation as the action plays out to the eventual hanging of Tsîlhqot’in tribesmen. The killing on both sides points to a shared pain and a shared responsibility that transcends and again questions historical fact as it relates to situations today. “In British Columbia there were no real treaties. Europeans arrived and claimed land, forgetting that there were people already living there. Many people came to the Northwest Coast, but the Europeans were particularly unwelcome because they brought small pox with them. The Tsîlhqot’in in particular reacted violently and groups of them began to attack the road builders who were attempting to connect to the goldfields of Barkerville to the Coast,” Douglas says. “In Klatsassin, there are no proper names,” he continues. “All the names are mis-attributed. So, there are only archetypes. Klatsassin or ‘We do not know his name’, never appears in the work himself much like the Judge to whom everyone is speaking, but whom we never see. Then there’s the Prospector, the Thief, the Constable, the Deputy and the Prisoner. These characters are types, not particularities, and are more or less representative of their exchange value for one another. I also have based parts of the video on Rashomon by Kurosawa. In Klatsassin the

Woodcutter from Rashomon is now a Miner. The Ronin becomes the Deputy and the Wife is now the Prisoner. These roles overlap in time. In fact, the languages

in the film are also a convergence. There’s Tsîlhqot’in, Chinook, German, French, English and Cantonese.”

Douglas states: “This way of creating ideas may have stemmed from an experience when I was just out of art school, working at the Vancouver Art Gallery as a media tech by day and as a DJ weekend nights. I quickly discovered how easy it was to make something new out of pre-existing material by editing and re-contextualisation. So, as a selector and occasional re-mixer I learned the lesson of the assisted readymade. What’s interesting about the readymade is that

the object retains the potential of its previous existence, be it music, a story, an image or some manufactured element. Its history remains there in some way, only in a new context.” Douglas’s photography stops the viewer for a more detailed moment adding further dimension to the stories. He creates the images to begin the process of his storytelling allowing him to study the environments

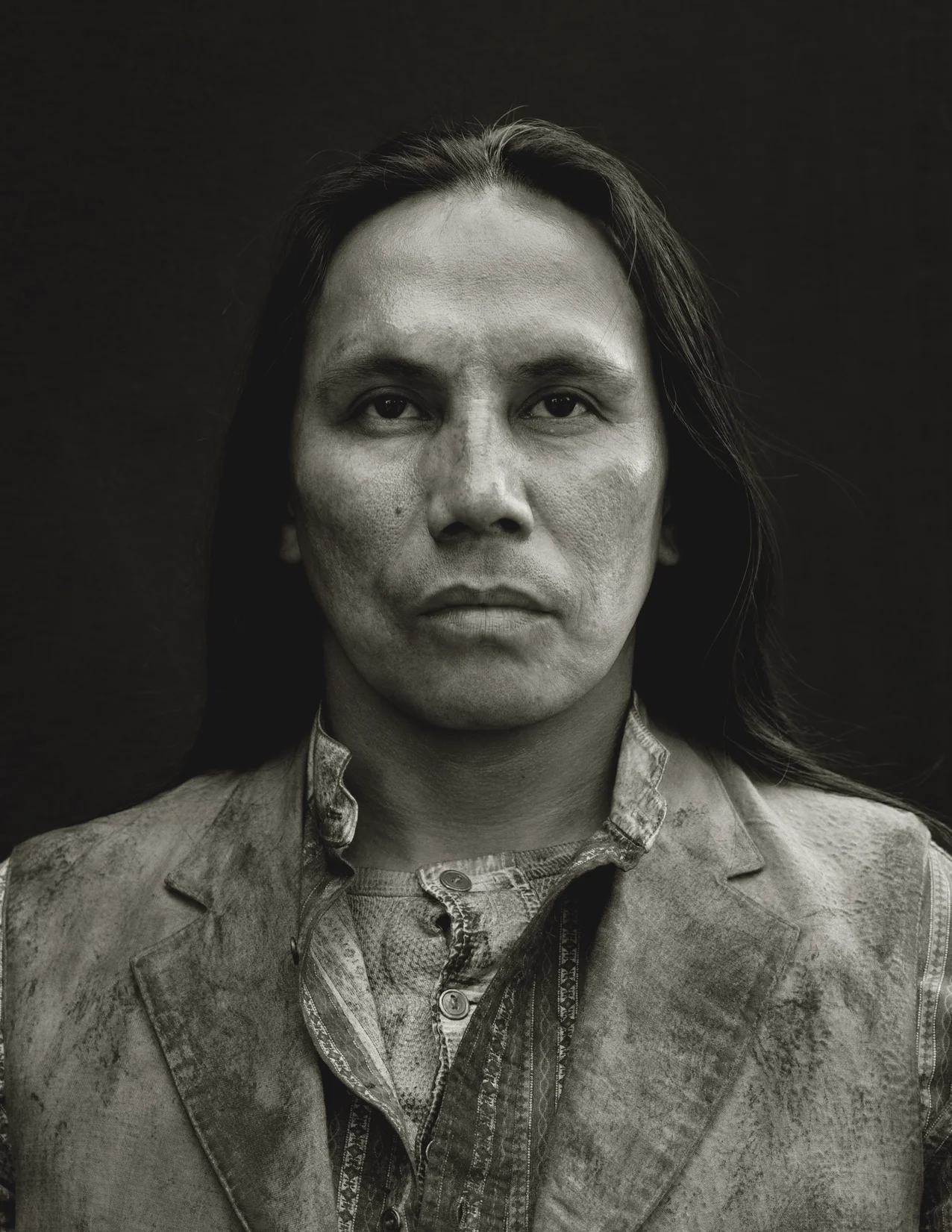

for his films. “When I begin working in a new location, I don’t necessarily have a predefined program or fixed idea of the quantity of the photographs I will need to make. Usually I can’t make a decent photograph until I understand what I am looking at, and its context, and in the end the final collection of images provide a context for themselves. That is how I know when I have completed a body of work. The images add another layer to the films and videos. After all, moving pictures are always transient. With photographs, you can pay more attention to detail. There are things that you can do in the photographs that you can’t do in video and vice versa. The two media supplement one another,” he says. For Klatsassin, Douglas made portraits of the main characters. “I shot the portraits as a photographer might have in the 19th century, with a view camera in black and white. We shot in a makeshift studio consisting of a black cloth facing the northern sky. Between takes, there was just enough time to work with the actors in costume,” He explains. Douglas also feels Klatsassin reinforces issues inherent with the repetition of history while questioning whether this repetition is avoidable or not.

Throughout human time, situations continue to occur where societies and civilisations clash over land and the value it holds. “There are always local manifestations of global conditions. And contemporary events that ‘rhyme’ with

those in the past. In the 19th century, an aboriginal people were displaced, or at least disrupted, by other peoples, Europeans, who wanted to take the most valuable commodity in the world out of the region, gold. The Europeans were not welcome, so there was an insurgency. And there’s the image of a prisoner with a bag on his head. If you replace gold with oil in the scenario above, it becomes clear that lessons that should have been learned one hundred years ago have been either ignored or forgotten.” In a way, the readymade has become human nature or the very inclination to forsake improvement and consciously and unconsciously settle for the eternal entrapment of repetition. Douglas leaves us self aware and wondering if we are capable, if not desperately responsible for causing some kind of change, whether it be big or small, that will move us forward without allowing us to end up back where we started, again.

TEXT BY TYLER WHISNAND

© pictures: Stan Douglas

caption: Prisoner, 2006 from the Series Klatsassin Portraits