Ukraine’s geographical immensity – over 603,600 square metres – makes it the largest contiguous country on the European continent. While neighbouring Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia to the west, Belarus to the northwest, and Romania and Moldova to the southwest, its eastern and northeastern plains meet the borderlands of Russia. But even today certain periods of the country’s early history cast shadows over its impressive geography.

After undergoing numerous changes of leadership since the 14th century, Ukraine suffered divisions of its territories under the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. For years this instigated warlike scrimmages, likewise failed attempts at attaining independence, en route to Ukraine becoming one of the founding republics of the Soviet Union in 1922. Less than 20 years later, however, as the stage for a Nazi campaign against the Soviet Union, the capital city Kiev became the site for a massacre of Jews, whose bodies were dumped by the hundreds of thousands into the Babi Yar ravine. More years of warfare followed. In 1945 the Ukrainian SSR became a founding member of the United Nations, and 46 years later, after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, the country gained its independence in 1991. But during the years preceding independence Ukraine was the main arena in which Moscow and Washington fought their Cold War – a state of political-military unrest and overt economic competitiveness between the Communist and Western worlds, spanning from 1946 to 1991.

If one were to condense and indeed estrange the aforementioned data by putting it inside a trash bag – in the form of 10,000 black-and-white negatives found in a former newspaper building and later developed to images of people and events during Ukraine’s Cold War period – this would give a rough idea of the multifaceted allure of The Cold War in a Trash Bag, Burkhard von Harder’s photo-project initiated in Ukraine and completed in Germany.

For this project the German photographer, also a filmmaker, functions as a visual worker on two counts: a photo-researcher armed with digital technologies and a photo-artist likewise an objet trouvé (“found object”) collector. Fundamentally, Von Harder points out to viewers that the Ukrainian “intel” culminates in reflections on memory’s role in the perception of history, and that it subscribes to the notion of a great archive, which gathers together many different types of documentation and knowledge. In the photographer’s exciting book presentation of the Ukrainian images – namely a POD (Print on Demand) book, a popular self-publishing format – the sense of an archive initiates a series of philosophical and non-political debates. Von Harder’s photo-project gives rise to the kind of 20th century vanguard thinking that elevates such endeavours to what Foucault deemed a “repository of memory and the fundamental building-block of the present”. Currently, projects of this kind qualify as advancements in the field of artistic research. And Von Harder’s artistic research transpires on three levels at the same time: privately, publicly, and by chance.

In 2010, in Vinnytsia, Ukraine, when Von Harder entered the attic of a large, deserted building – that is, deserted save the studio spaces of a young fashion photographer and two rappers on one of the floors below – he discovered an abandoned “archive”. Riddled with cracks yet structurally sound, the building begged to be explored. And the photographers did so. While rummaging through the attic, they found several negatives scattered over the floor. This was only the beginning of their find. As they continued exploring the premises, they found more negatives strewn about the space, and their number rose to the thousands – all of them unprotected, left to waste, and in poor condition. Bagging the celluloid scraps and bringing them to Germany posed no problem. Thanks to forthcoming representatives from Ukrainian cultural agencies and museums, Von Harder could cross border after border with the deteriorating material and finally subject it to post-production and image-making processes in his own country.

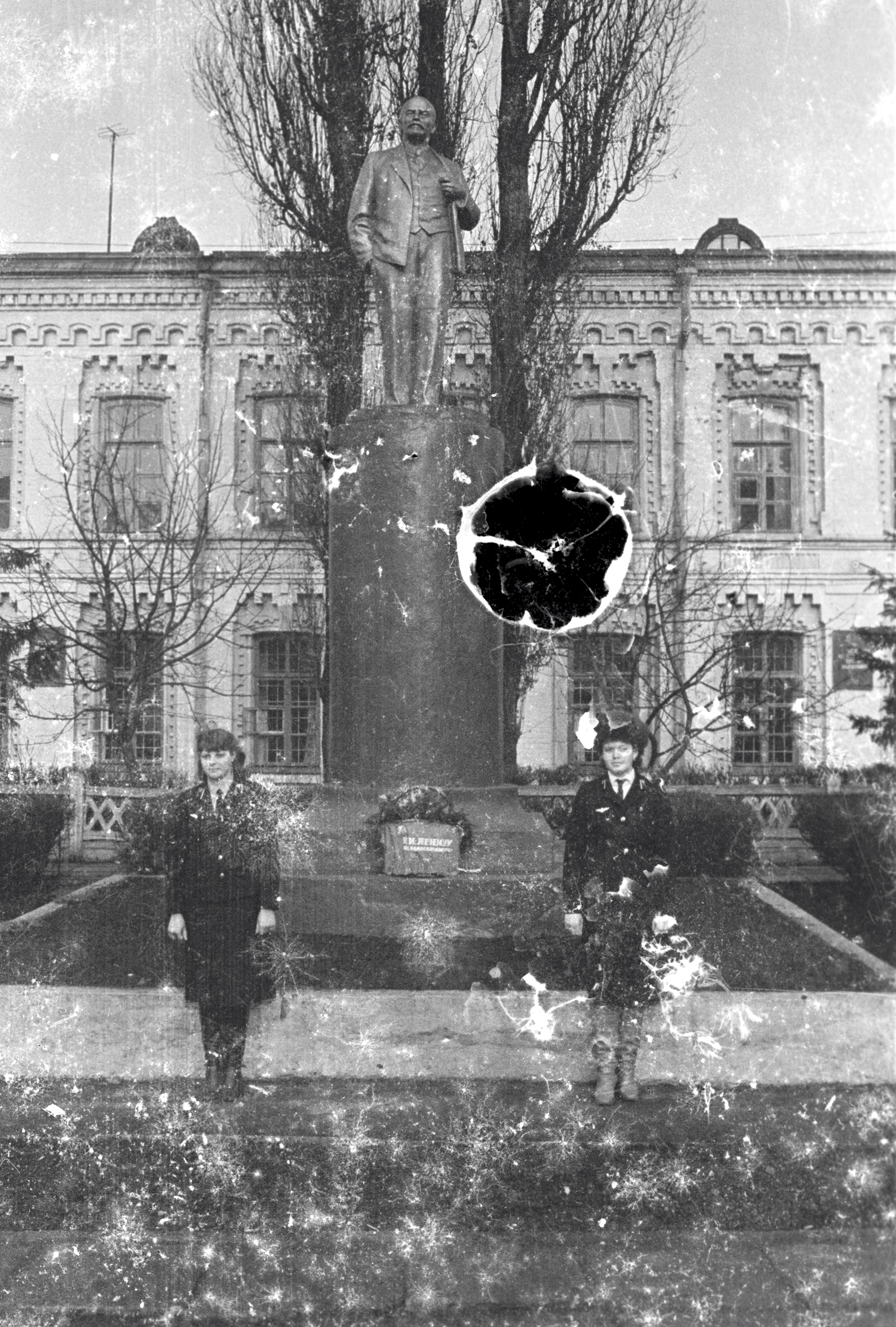

The found images of Von Harder’s Cold War photo-project build an archive at once nostalgic, anonymous, and hard to explain. While appearing to capture local Ukrainian citizens from every walk of life, they make unexpected departures into what seem like rigid political situations and equally rigid cultural ones. Intended or not, an offbeat humour wafts from the men’s East bloc attire and (Western) “Monkees” hairstyles, and the specific charm of the made-up, young women was probably never catalogued in any Western manual of style from that period. But private and public auras aside, what reigns is the overall visual quality and suggested cinematic patina. Moreover, apart from being pieces of photojournalism shot by unknown photographers, the images seem twice removed from the reality of most viewers: once for documenting an unknown culture, and again for documenting that culture under the influence of a unique time period. This is where Harder’s project shines brightest: when it welcomes the gaze of viewers unfamiliar with Ukrainian history and Cold War details. With digitalised inventions of his own design, he captures what he calls the “zero hour” between Communism and independence in Ukraine – and goes on to take full advantage of this archive: by evoking an entirely new archive from an old.

Von Harder’s love of image-making salvages found material as well as encourages viewers to construct mental archives of their own. To work with such humane if inconsistent images would be thoroughly enjoyable, were it not for the disturbing ebb and flow underneath: the sometimes tranquil, sometimes exploding picture surfaces. In unpredictable waves, many of these remarkably sober portraits and documented events become electrified by photo-corruption that bedazzles the picture frame like crude Christmas decorations. These visual intrusions leave the simplest of social situations over-dramatized by the likes of superimposed star constellations and gelatinous forms fringed with roughness, or by amoebic shapes almost close-ups of bacteria and surface abrasions resembling knife wounds when developed. Where corruption overpowers the image the implied documenting of a Communist society dissolves to the hazy psychodrama of a de-politicized European anywhere.

In Von Harder’s own words, his weeks spent visiting Vinnytsia reminded him of life in a small town in Southern Germany, a remark which significantly links with many of his previous projects, especially those he describes as “family research with artistic inclinations.” Such projects focus on researching and discovering private histories, and, in relation to World War II, flushing out human and political sympathies as well. In general, they chart the movements of family members in given time periods and locations. In his Cold War project, however, Von Harder’s interests feel more historical than familial (more European than German), and appear directed at a series of Ukrainian impressions in the name of archive production. What comes to mind is the inventiveness of Von Harder’s 2009 multimedia project Resurrection of Memory.

While keeping a chilly distance from human forms, the cinematography of Von Harder’s film The Scar anticipates the archival state of mind of his Cold War project. If nothing else, its scenes reflect and reflect upon a presence beyond memory as well, while appealing to photography’s convincing ability to present a possible truth or memory. And, via quotes and descriptions, Von Harder also reminds viewers of the new concept of memory at large today – as posted in the 2011 call for submissions to a video project sponsored by the Studio Marangoni and the Celeste Network: “[…] memory as a repository of a single, absolute truth, has been replaced in our information age by the notion of many memories: micro-truths without universal authenticity […]” Concepts of this calibre influence so-called history production and trigger an engaging, cultural phenomenon in the here and now. They serve to remind us that popular philosophy – with theories by the likes of Derrida, Foucault, and Wittgenstein – is bejewelled with notions focused on what the archive is capable of.

But when considering Von Harder’s intuitive, less analytical side – the part of his thinking receptive to the idea of technical errors aiding the creative process – an entirely different visual theatre materialises. (Was it not Derrida who implied that well-executed failures have more value than successes?) As narratives, the pockmarked photographic images suggest the choppy, psychological playfulness of Hans Richter’s experimental film Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947), the crowning difference being that they never lose track of real social criticism. Furthermore, the Cold War images surpass the initial fascination with the objet trouvé, point to a sense of private theatre, and welcome discussions on art movements like Art Brut, Art Informel, and other strains of Raw Art. Along these lines it fascinates how Von Harder’s digital processing transforms photo-corruption imported from Ukraine into photographic “abstract painting”. In certain exposures the accumulations of shapes and distortions ravage the images like a photographic leprosy, leaving viewers little to grasp in the way of “classic” black-and-white prints. Instead, the photograph is reduced to an artwork shaped by deleted references to time and place: a pseudo-social vision trapped in strange nets made of blurs and scratches. Ultimately, if the intention is to research the face of Ukraine’s Cold War period via a single location, the alter ego of the undertaking is surely this painterly implosion of content and imagery. In addition, its jarring appearance corresponds with Harder’s ongoing interest in expressing the hidden layers and concealed aspects of his subject matter.

In the image-making process it hardly surprises that these pictures recall Germany’s history, along with the massive German word Vergangenheitsbewältigung, meaning “the activity of coming to terms with the past”. In this case, however, what applies most is coming to terms with national unity, invisible divisions, and European integration. With these issues in mind, the depictions of what might be party members posing for ID shots or simply relaxing, scenes boasting Communist artefacts in the background, and images of nervous schoolchildren beside heavily-decorated officials do, in fact, recall some of the political fanfare and social peculiarities of the former GDR. In this context, many “classic” East bloc likewise Cold War details seem challenged by a kind of political Down’s Syndrome, which produces a recurring “look” based on specific types of clothing, objects, and architecture – on characteristics that could only come about under such “Eastern” conditions.

Just the same, the project’s artistic accent is much stronger than its political one. For that reason too, the Cold War images frequently submit to the photographer’s artistic, slight of hand. Von Harder thoughtfully couples or separates his subjects and found models. He juxtaposes the negative and positive images of the same exposure within a single “book spread”. He structures the composition using the fierce-looking scars in the film material, and gives as much weight to a private or official gathering as he does to a playfully solarized shot of proud bodybuilders sitting, squatting, and standing in rows before the camera.

Most significantly, perhaps, Von Harder presents the found Ukrainian material in photographic duets. This clearly adds to the prevalence of research, as if he were telling viewers that the photographic moment is being “studied” from two vantage points at once. (Even photographs Von Harder couples with empty spaces somehow fall into this research-friendly category.) This contrived, doubled oneness presents simple portraits and images taxed with photo-corruption side-by-side, but also offers viewers a potential “before and after” situation – or better still, an archival “then and now”. The latter situation surpasses the former if only because Von Harder’s projects are always so exquisitely constructed in the here and now.

TEXT BY KARL E. JOHNSON