Saul Leiter, was a very humble man who would rather talk about artists and writers he enjoyed than himself, he was happy to share his memories of other photographers he knew well such as Diane Arbus, or his passion for French photographers such as Boubat or Lartigue who he admired.

Back in 2009 Eyemazing encountered this wise artist in New York City and found him to be both passionate and witty when talking about his life and work.

Sarah Baxter: Was the show you had in Paris at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson the first show you had in France, and even in Europe?

Saul Leiter: Unlike a lot of other photographers, I didn't have shows and books and all these things. I always thought that books were for other people. I didn't expect to have a book. I didn't expect to have anything! I didn't know what would happen with my work. I came into the Greenberg Gallery and after a while I began to work with Margit Erb and we became good friends. She is a person who likes to do things. And I am a person who likes putting things off until tomorrow, or next year, or the following year! I had a book published on colour, Early Color (Steidl, 2006), that was the first book. And then, Monsieur Delpire—who years ago wrote me a letter saying he'd like to do a book on my work—contacted me again. And because I am not always very serious, I wrote him and said that I felt very honoured to be part of the Photo Poche collection and that when it was published, I would buy two books! [Laughs.] It's been very nice to see that work I have been doing for 60 years is receiving attention. Sometimes I think too much attention! I have a view of my own abilities, but I also admire great things done by others and I consider my own achievements not to be heroic, although some people admire it greatly. I don't like to admire myself. My father was a great scholar, he was a Rabbi, and he knew the Talmud by heart, he knew thousands of books, he was a linguist. So, compared to my father, I've never taken myself too seriously. He was part of a world of great scholars. And in some part of my brain, there's a great admiration for scholarship and learning. My father hoped that I would be a scholar but I betrayed him! I didn't do what he wanted me to. So sometimes I look at myself the way he looked at me… With disapproval! [Laughs.]

SB: How did you decide to become a photographer?

SL: I never decided anything. I studied in theological schools then I left home and I came to New York and I never finished the university, I never finished certain things. I didn't know what to do. I didn't know how I would live. My mother sent me money, kept me alive for many years. Eventually I was friendly with Richard Pousette-Dart who was a painter. Then I began to do photography. I would occasionally make some money. I'm very lucky: I don't remember my early struggles! My life is lost in a mist, in a fog... I would occasionally keep little bits of diaries but then, when I moved, they disappeared and different things got lost.

SB: Isn't the type of photography you make a way of keeping a trace of things?

SL: No. I had no philosophy about photography. Some people have a vision, an idea. I think, for instance, that at a certain point Diane Arbus was out to explore the strange aspects of life, maybe. For example, she writes in her book that she was in England and she hadn’t found anything weird yet. She was looking for weirdness. I never had a specific approach to photography. There are many photographers that I like. I love Kertész and Atget. I like Brassaï, Boubat and the French photographers. But I was just bumbling along [laughs]. I didn't know what was going to happen. Then Henry Wolf at some point gave me work in Harper's Bazaar. I also had some things at shown at the MOMA (Museum of Modern Art) in the show of Steichen's, and at the time, I didn't appreciate that it was a very special thing to have my work shown at the Museum of Modern Art, because I never had a sense of a career. Having a sense in a career can be very important to an artist. Some people have it, and some people don't. And I definitely don't! My friend Henry once said to me that I had a talent… for ignoring opportunities!

SB: You did fashion photography…

SL: I did fashion photography, I did advertising… I tried to earn a living, and was not always successful! I had a studio at 156 5th Avenue for a number of years. And I worked for different people and for magazines. Some of my favourite pictures I did with Soames for Nova, which is an English magazine that I liked a lot. And the Art Director of Harper's Bazaar saw my pictures for Nova and said to me: “Why don't you do something like that for us?” So I gave her an idea a few weeks later and she had forgotten what she had told me and she said: “We can't do that! We're Harper's Bazaar!” and that was it! Sometimes I made some money. Sometimes I was very impractical. I bought prints, I bought certain things. I love the works of Bonnard and Vuillard and owned some. I also had a little collection of Japanese prints. I think that the Japanese explored many ideas long before Western artists ever did.

SB: You made photo portraits as well?

SL: I did them for myself. Magazines at different points had different ideas of what I was. The New York Times gave me work as a children’s photographer. Everybody had a different idea. Well, Avedon did portraits. If something needed to be done, he did it! So there were areas of photography that I might have enjoyed working in, but I wasn't considered proper.

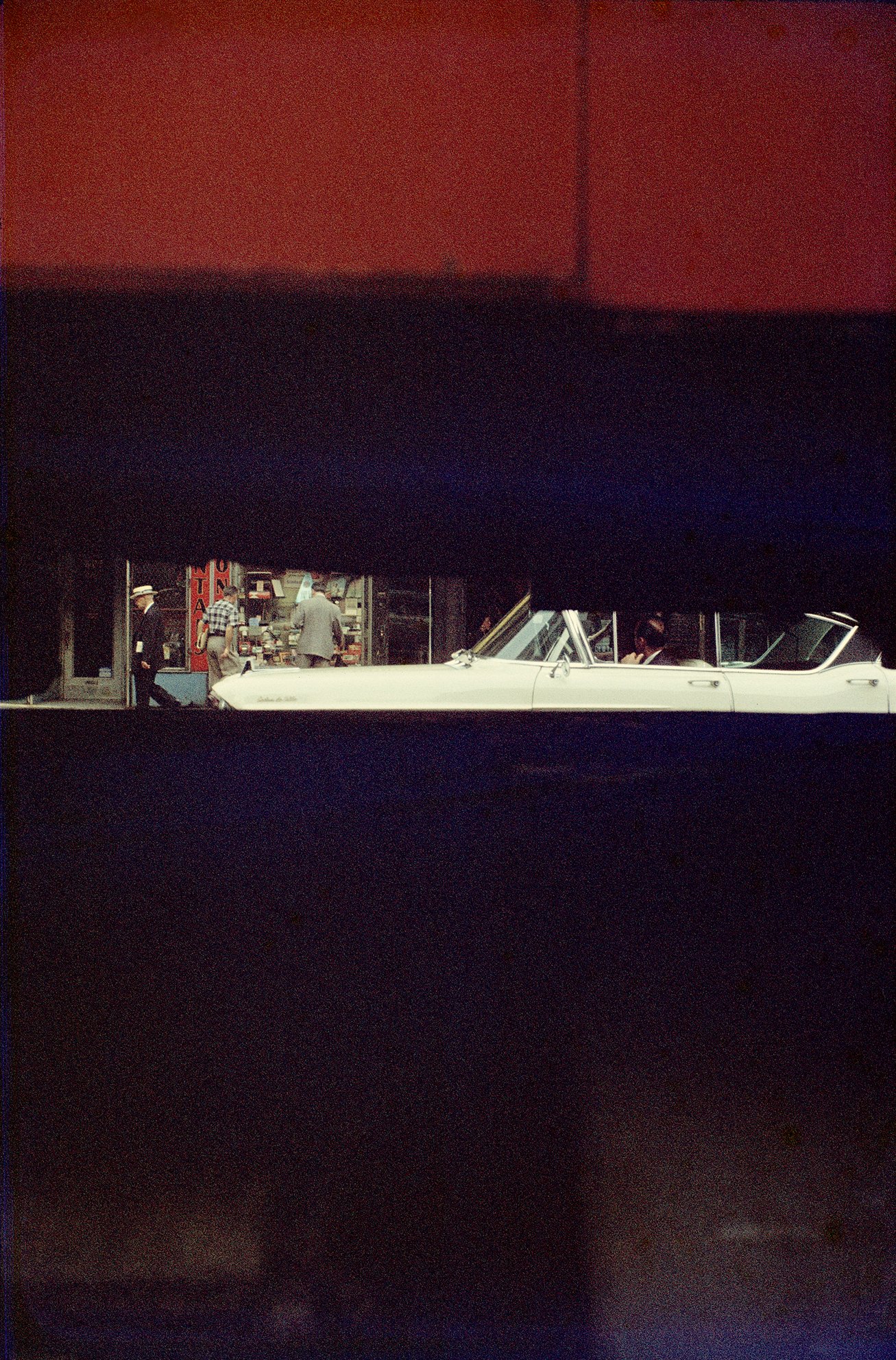

SB: But you did also a lot of street photography?

SL: I did that for myself as well. That was personal work. I enjoyed doing that. The street for me is almost like a ballet. They are all these people moving around, freely, aware of each other and unaware of each other, and twirling and swirling around… And of course you don't have to deal with anybody, you don't have to ask for permission. Although I think it's become more difficult to be a street photographer. But I did things that I liked doing. I'm going through my work now and I discover things that I never printed, that I think are maybe interesting. Sometimes I didn't have the money to print everything. And sometimes I didn't see. Sometimes a photograph needs time. Time is sometimes on the side of the photographer. What seems to be prosaic and ordinary in a given moment sometimes, with the passage of time, becomes exotic.

SB: Some people have discovered your work only lately.

SL: Maybe I should have been more organised! A lot of my negatives were destroyed in a flood and there were two fires where my files were kept, and the fireman came in and sprayed the place and a number of things were badly damaged. But I figured that if I had everything I did it would be terrible; at least I don't have to deal with all of it! Pasternak said something like one should lose a quarter of one's work. I think I lost more, and I think that's good. People who keep everything amaze me. I keep a lot and my house is a mess, a disgrace… I'm ashamed to have anyone come in now! (Ha, but not really.)

SB: You did some of the prints yourself?

SL: I don't print right now. I did a lot of the little prints that are shown at the Howard Greenberg gallery, those are mine. Sometimes I try to get a look or a feeling in a photograph. It's very difficult. When you do a photograph, then someone makes a print, someone reproduces it, there are all these steps in the course of which whatever it was originally gets lost. So if you work, let's say for magazines, you get used to that.

SB: You coloured some of your prints?

SL: Yes, you are referring to the painted photographs. I have different versions of why I started doing that; I don't know anymore which is true. I once had a print on a counter and I was painting and paint got on it and I think that's how I started to paint photographs… But these days I'm not sure if it's true or if I just made it up!

Text by Sarah Baxter, ©EYEMAZING foundation

©pictures Saul Leiter, Courtesy Saul Leiter Foundation, Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York and Gallery Fifty One, Antwerp

The American artist Saul Leiter (1923–2013) became enchanted by painting and photography as a teenager in Pittsburgh. After he relocated to New York City in 1946, his visionary imagination and tireless devotion to artistic practice pushed him to become one of the iconic photographers of the mid-twentieth century. An innate sense of curiosity made him a lifelong student of art of all kinds, and he retained his spirit of exploration and spontaneity throughout his long career, in both his fashion images and his personal work.

www.saulleiterfoundation.org