The Visual Rhizomes of a Social Conscience

If the cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words has any meaning, that meaning is grounded in the rhizome of history, the spreading roots which come together and form a network of associations at the site of the image like a nerve cell. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei's gift—illuminated by the impressive array of 230 of photographs taken during his sojourn in the New York East Village, and selected from over 10,000 images archived by Three Shadows Photography Arts Centre in Beijing—is the keen sense of social and cultural acuity that enabled him, even as an outsider, to capture seminal moments that root his images in the dense, chaotic network of meanings, ideas, conflicts, struggles, aspirations, and contradictory values that embody the life world of a particular place in time.

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957 in Beijing, but spent much of his childhood in the remote northwestern province of Xinjiang where his father, Ai Qing—a prominent poet—was among the many intellectuals sent to engage in labour reform as a result of purges following the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957.

Ai Weiwei's staunch independence, resilience and unrepentant critical stance towards the state of society and the structure of power, were forged in the crucible of early childhood experiences. Watching his intellectual father persecuted for writing "the wrong kind of poetry," forced to clean toilets, and not allowed to write for two decades, left a scathing impression on the young artist. It was not until 20 years later that his father was exonerated and the family was able to return to some semblance of a normal life in Beijing after the Cultural Revolution had ended, and Reform and Opening had begun.

As Western culture began to trickle back into China in the late 70s, young artists like Ai Weiwei were electrified by the variety of expressive forms in circulation, as well as tempted to test the boundaries of acceptable expression in public in the new era of tentative reform. Art became a major part of this process of cultural testing that helped broaden the horizons of the State-dominated public sphere. In 1978, Ai Weiwei was among the small group of experimental artists who founded China's first avant-garde art collective, "The Stars" (which included Huang Rui, Ma Desheng, Wang Keping, and other major artists still noteworthy today). At a time when people were still wary, following the tumultuous and repressive decade of the Cultural Revolution, the daring and unauthorised public exhibitions and activities on the part of "The Stars" was of seminal cultural significance, and played a role in setting in motion a generation of visual pioneers who began experimenting with Western art forms and media, while trying to come to terms with China's recent past and to rethink the role that art and cultural production could play in shaping the trajectory of its future.

When the opportunity arose to study in the US, Ai Weiwei set off for New York in 1981, spending time in Berkeley as well, before returning to Beijing to be by his father's side on his deathbed in 1993. His experience abroad fortified his critical nature, and was supplemented by the quintessential American belief in the power of the individual to shape society. Since his return to Beijing, Ai Weiwei has consistently played the role of contentious, public intellectual and member of China's cultural vanguard in the capacity of critic, curator, architectural designer, and innovative multidisciplinary artist.

As one of the most high-profile Chinese contemporary artists alive today, and recipient of the 2008 Lifetime Achievement Award in Chinese Contemporary Art, Ai Weiwei's work has been shown at major exhibitions including the Venice Biennale (1999), 2nd Guangzhou Triennial (2005), 2006 Biennale of Sydney, Documenta12 (2007), Liverpool Biennale (2008), and a solo show at the Mori Art Museum is slated for summer (2009). His role in conceiving the design of the Olympic "Bird's Nest" (the Beijing National Stadium) in collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron, his co-collaborators in the Venice Biennale of Architecture (2008), has earned him a name that resonates far beyond the reaches of the art world, but it is his brio as public intellectual that is perhaps the pulse that reverberates throughout the corpus of his work.

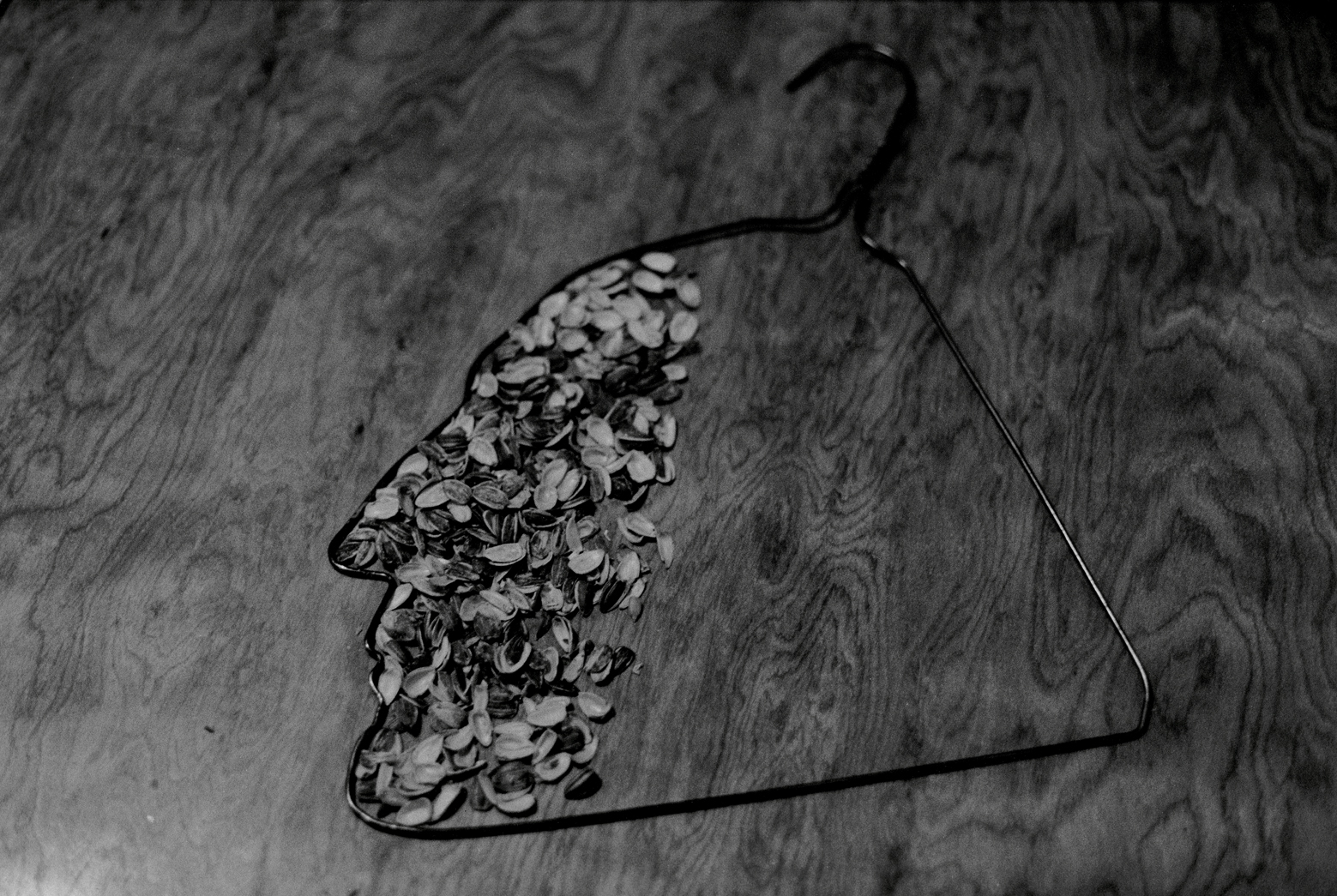

While Ai Weiwei's installations and sculptures often feature ready-mades that he has transformed with a conceptual twist, such as shoes, furniture, urns, antique doors, bicycle parts, and more, hinting at the deep impact of Duchamp on his work, it is his photography that reveals most profoundly the presence of the person within the artist, the identity of those two things, and the extent to which he takes the role of public intellectual seriously.

RongRong (Three Shadows co-founder and celebrated photographer in his own right) had been a close friend since Ai Weiwei was actively involved with the performance art scene at the Beijing East Village where RongRong lived in 1993-1994, and spearheaded the labour-intensive project of archiving the over 10,000 negatives that had been taken during the decade or so in America.

In Ai Weiwei's Bleeding Protestor: Tompkins Square Park Riots, the rivulets of blood streaking down the face of a pony-tailed man, darkening his T-shirt in a spreading stain, look more like experimental ink wash than police brutality. Yet the outraged glare, the mouth cocked open in mid-chant, and the fury, or quiet horror of his fellow protestors is anything but artifice. These men and women are for real. It is 1988 and this riot is the culmination of months of tension in New York City over the rights of the urban poor to shelter. The park had become a magnet for homeless people, and after each police roust, the legions of hungry, tired and poor, would re-encamp in ever greater numbers, supported by a vocal coalition of progressive citizens disgusted with the go-go 80s shameless, selfish materialism, gentrification and disregard for those unwilling or unable to ascend the social ladder. When protestors ignored the police curfew, the officers responded with indiscriminant violence, and the once-peaceful protest ignited into a raging riot that drew condemnation of police brutality across society.

Images of glorious, bouffanted drag queens, reinventing Diana Ross' legendary "I'm Coming Out," during Wigstock in 1990, root us into an emerging gay rights movement that is still one of the major civil rights issues of our time. The specter of homeless people sleeping beneath lucrative, commissioned public art works, speaks of the contradictions in an economic system rooted in unsustainable, endless consumption (until that consumption comes to a sudden end and we find ourselves where we are now). And the angry protests against the first US Gulf War in 1990 remind us of the presence of the past in our collective present and future.

Ai Weiwei is sometimes portrayed as playful punk, slick manoeuvrer, even swaggering ego. At odds with these glib portrayals, however, is the fearless earnestness and trenchant sensitivity revealed in the continuity between his preoccupations as a young man incessantly shooting photographs while living the New York East Village, and his activities since returning to Beijing. He played a mentoring role in the performance art hotbed known as the Beijing East Village, until the crackdown that dispersed the community in mid-94. His samizdat publications of the White, Gray, and Black Cover Books (1994-1997) offered critical discourse and introduced then-unknown seminal artists. In 2000, he co-curated defiantly uncommercial works at the landmark Fuck Off group exhibition in Shanghai. After helping design the Olympic "Bird's Nest," he became an outspoken critic of the urban "cleansing" that flushed the labourers who had built the New Beijing and Olympic facilities out of the city, like detritus, before the Games. And his prolific blog entries, rife with wrathful judgments upon the pathologies of our times, alongside the endless parade of documentary photographs that Ai Weiwei compiles almost compulsively, provide a symmetrical textual counterpoint to the enormous body of photography from the New York years and beyond.

In spite of his meteoric rise in recent years, seemingly mirroring the skyrocketing fortunes of Chinese art in general, Ai Weiwei is anything but a metonym for mainstream Chinese contemporary art, and attempts to portray him this way, miss the point—and the power—of his work and role as public intellectual. And while his sculptures, installations, and interventions have been showcased worldwide to critical acclaim, it is this newly unveiled and vast body of photography that offers the clearest metonym of the artist himself.

In an art scene that has grown systematically averse to genuine political critique—a hangover collectively shared by the broad mass of society and much of the intelligentsia—Ai Weiwei's pointed invective against social injustice and abuses of power is unsettling. In contrast many of the China auction-house darlings discovered in the mid-90s, that foreigners (the only market for contemporary art at the time) fetishised easily-recognisable, easily-digestible, iconically "Chinese" political symbols, were by the new millennium well-fed, well-shod, complacent assembly lines, churning out their own "brands"—Chairman Mao; red stars; cute girls in Red Guard uniforms and pigtails; sad-eyed families rendered uniform by political oppression; masked faces that bespoke a tragic double-life under communism, all popified versions of cultural revolution iconography mismatched with Western brands. This became so deeply entrenched in the maintenance of the status quo that it is now perverse to look to their work for critical optics and subversive sentiment.

Indeed, since the mid-90s, China's art scene has been an environment where genuine political critique (as opposed to manipulative foreigner-wanking) was seen as passé (so late 80s!), even naïve, and the province of the foolish hornet's nest-stirring few who hadn't figured out that "to get rich [really] is glorious," and the most vanguard expression of patriotic pride in the fatherland.

In this context, Ai Weiwei's New York photographs offer a prescient visual harmony to his blunt pronouncements about the character of cultural production and art in today's China—"still the subservient accessory or sacrificial object of politics"—and the role of art and the artist caught in the closing wedge between post-totalitarian State and globalised, mendacious market—"we live in an era in which the system of values and the possibilities of critical judgment are extraordinarily chaotic and confused," he declaims. Even so, he sees a refusal to cede for speech and action in the public sphere and the power of individuals to shape the course of history.

When asked if he worries about the danger of becoming a casualty of repression like his father he offers a shrug and a smile. "The way I see it," he says, "this is my life, I don't have a second life, and I don't have a second kind of life. I think that in this respect, every person has a responsibility.

TEXT BY MAYA KÓVSKAYA

Courtesy Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Beijing