John Waters, Baltimore’s “Pope of Trash” and the filmmaker behind cult classics like Hairspray and Pink Flamingos, makes more than movies. His contemporary art, a collection of montage photography, sculpture, and self-portraiture, is as bizarrely humorous and intelligent as his films. Rear Projection, his latest exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, is a bawdy feast of good-natured parody. In what follows, Waters explains how bad film stills make great art, why contemporary art hates people, and what it’s like to pose as the Provincetown Town Crier.

Clayton Maxwell: On the Gagosian website, you are quoted as saying, “There is no such thing as a bad movie frame. It can be a terrible movie but in the art world it can be seen in a totally different way.” Could you explain this?

John Waters: When you go to see a movie in the theatre you are thinking of the whole movie, the plot, and the performances throughout. If you are seeing it in the art world, as I am especially, and it doesn’t work in the movie world, you can take a still, which is basically 1/24th of a second, and think of it as a still to be printed. So you can look at whatever your want—the lamps or the rugs. Or take that image and edit it in with one from another movie and that turns the whole narrative around. And sometimes it’s the opposite of what it was saying in the original movie. I am really writing with these images what I notice in a movie. With two of the pieces in this series, The Penmark Collection and The Rope Collection, basically I am sneaking into a movie like an art thief, when none of the characters, the writer, the directors, the crew, when no one is looking, and taking the art off of the wall and taking it back to my home and then putting it into a gallery. That art has nothing to do with the plot. You are not supposed to notice it. No one talks about it. It is never featured for long on the screen. Therefore, to me it is the most important thing when I am watching the movie with an artistic eye.

CM: So it can be a pretty bad movie, but because you are free to do whatever you want with the stills, you can transform it.

JW: I love bad movies sometimes. Bad, what does that mean? Sometimes I think movies that win the Oscars are bad. Bad is an opinion. What I’m saying is, you can take any movie, one you love or hate, and subvert the original meaning of that movie by putting it up with another movie or putting it in a different order or editing out the details. Like a failed publicist for a movie who would be fired the first day—because the stills that I take are ones that would get no one to see the movie. They might get them to buy it and take it home from an art gallery. But that’s not what a publicist is supposed to do. And I am always convinced that nobody remembers movies, they remember the stills that made the movies famous.

So in that way I am trying to subvert all the insider knowledge about show business, but in a joyous way. Because I always make fun of things I love. I never parody the things I hate.

CM: Yes, and that’s what makes it more appealing to me as a viewer because it doesn’t come off as mean-spirited.

JW: No, it isn’t mean spirited, not at all. Even the Smile Train people called me. (Smile Train is the world’s largest cleft surgery charity.) I explained to them I parodied them because I love them. To me they are stars, too. Edith Massey could have been in the Smile Train. I could have switched stars.

CM: How did you come up with the Smile Train idea?

JW: Well, I get the ad in the mail everyday almost. And there are billboards of those children. They are as big as Jerry’s Kids ever were.

In the charity world there are stars, also. If I saw one of those children on the street I would recognise them I think because I’ve seen them so often. They are promoted. And I am not saying that’s wrong, I’m sure that charity does a great job. But at the same time, there are stars in every world and when I put them together I hope I am commenting that they are the same in a weird way.

CM: Yes, those Smile Train images really stick in your head.

JW: Yes, they do. Like did you see the new woman today who got a new face and they showed this great improvement? It was staggering to me. They showed the before-and-after. Have you seen those pictures?

CM: No, I haven’t.

JW: Oh, look on-line. The woman who got a face-plant. You can never top what comes in the next day’s news.

CM: And I love how you do highlight that they, the Smile Train kids, are celebrities, too. It helps to rethink my ideas of celebrity.

JW: Every business has their celebrity. Every movement has to have a star, has to have somebody that sells it, that makes people be interested in it.

CM: One of my personal favourites in this series is the Town Crier. I read that it was an embarrassing experience for you.

JW: Let me tell you something. I live in Provincetown. Every summer there is a town crier. I remember they had one town crier who children ran from he was so scary. They’ve had a drunk, one who was a pervert…they’ve had a gay one. And the one they have now is lovely, and he’s good at it—he’s involved in the Broadway world, he’s an actor. And I see his joy every day in doing it. A long time ago I saw the scary town crier in the cleaner picking up his outfit and his regular clothes with the plastic over it and something made me crazy about that. So I was really thinking about what it would be like to be the town crier. So I just went over to the town crier’s house and asked him if I could borrow the outfit. It was so humiliating, but he was very lovely and very kind. The outfit is one size fits all, you’d be surprised, except for the tights I had to buy and I think the buckles on the shoes. And then for me, to do this in Provincetown, where generally I’m really well known because I’ve been there for so many years, but I’m always on my bicycle so no one can really stop me. By the time they say, “Hey, that’s John Waters” I’m already down the street… Well, to actually walk downtown at the height of the season and be dressed as the town crier was something really frightening for me to do. I got dressed in my apartment and looked in the mirror and said, “Am I actually going to walk out of the house like this?”

The real town crier wears the outfit with great authority and I wear it with great mortification. Because every day I’m dressed as John Waters and he’s dressed as the town crier, and in a weird way we have the same job because a lot of people know who I am and a lot of people know who he is. But maybe it would have been better if he had dressed as me at the same time. That’s what we should have done.

But I thought, “Well, I have to do it.” I have my art gallery in Provincetown, the Merola, and Jim, the part owner, picked me up in his van across the street. But I still had to walk across my yard and then I saw my landlady gardening, and she just looked up and the expression on her face— it said, “What in the hell could you possibly be doing?” It was a great moment because she was totally bewildered. That was the only person I made eye contact with when I had it on. So we went downtown. We had it all set up for the shoot. I jumped out of the van, took the shot then jumped back in. I couldn’t make eye contact with anyone in that outfit. It was a new exercise in humiliation for me; it was an S and M experience.

CM: That’s crazy that you should be so embarrassed. You are John Waters—aren’t you used to dressing up?

JW: But not as the town crier, though, not in a pilgrim outfit. I can dress like me everyday. But I can’t get dressed like the town crier. It’s just a different kind of drag. And I love the town crier. And he loves doing it. And he doesn’t look silly in it. But that’s a whole different thing. He wears it with confidence. I wore it like bondage.

CM: And is that a good experience?

JW: I did it once. I don’t think I’d ever have the urge to do it again. Although now the town-crier is my friend, and whenever I have parties he’s there and people ask, “Why is the town crier at your parties?” Because I didn’t really know him before.

CM: Tell me about two of my other favourites pieces, the sculptures of the bottle of Rush and the La Mer face cream.

JW: I can tell you about some of the great reactions I’ve gotten. I was giving my lecture at the 92nd street Y with Rob Storr, showing slides of my work. And just coincidentally in the audience were three of the women who run the La Mer company. They were stupefied when they saw it. So they came to the opening and brought me a $1000 bottle of La Mer. And the foundation bought the piece, which I loved.

And then I got a letter from the man who runs the company who owns Rush—and I always get paranoid at first that someone’s going to be mad—but he told me that he loved it and that he was sending me a lifetime supply of Rush. It looks great in the box. So many bottles. It’s so Warholian. Now every time I do Rush I need more La Mer, so I’m really set for life. The Smile Train called but they didn’t send me a facelift.

CM: It’s funny because I heard you once say that companies would not want any of their products in your movies.

JW: No, they’d threaten to sue.

CM: But now it’s reverse.

JW: It is a little reverse in the art world. I always said that the art world and the movie world are opposite in a way. In the movie world we have to pretend that every person in the world has to love the movie. And in the art world if everyone loved it, it would really be terrible. You just need one person to love it. Mostly it's completely the opposite. But I’m still dealing with humour and still dealing with the movie business in some way.

I use La Mer crème. It’s one of the few luxuries I really do give myself and used to feel guilty about, but not anymore. And I do use poppers, but not as much as I pretend. Am I making fun of them? I’m making fun of myself for loving buying them. But yes, I like those products.

CM: Are they as great as they claim to be?

JW: La Mer is. You put it on a burn, and it completely heals it. I must admit every time I buy it I think, “Now does this really work?” And then I think, “Well, how ugly would you be if you didn’t use it?” And Rush is the poor man’s Viagra. And on Viagra labels it says to never use poppers at the same time, but I have friends who say, sure you can. It’s a low rent high. But if it's a high that only lasts three minutes, how bad can it be? I’ve never heard of anyone having a bad popper trip.

CM: Moving on. In the montage Hetero Flower Shop, are you saying that no gay man would make arrangements that awful?

JW: No. I am asking the question, “Can a hetero man be a good florist?” And the results speak for themselves. I was trying to imagine, if there were a florist that was sexist and only hired straight men, what would the flowers look like? And then I recreated those flower arrangements, inspired from real advertisements. But those are the kind of flowers that most people want to get in Middle America. If I got them I’d be furious. I’d call the person who sent them and say, “Look, I really thank you for sending me flowers, but I’ve got to tell you to change florists.” I got the idea because of a friend who was trying to get a new florist. She called the florist and said to the guy on the phone, "Is there a gay man there?" And he said, “Yeah, I’ve got a couple in the back. And she said, “Well, let me talk to them.” She told me, “You know, I don’t want a straight man doing my flowers.” Is that acceptable sexism? Is it a hate crime to ask if your florist is heterosexual? I’m trying to really analyse the situation for its sexual politics.

CM: Can you tell me about the process of putting together a montage like Rear Projection? ["Rear projection" is a movie term for the process in which a studio-filmed foreground action is combined with a previously shot background scene to give the impression the actors are on location.]

JW: I found each rear projection shot. Matt, my assistant, looked at hundreds of ass pornos, and then we took the pictures of them and isolated them and zoomed in and took them out of different frames. Then Brian Gossman, who does all my photo retouching, he put them in. I conceptualised it. I’m directing and editing it. It’s all about editing. It’s hardly about photography. I use photography. But it’s not about photography. That’s the least of what it’s about.

CM: Are you ever surprised with what you discover through the process? Does it ever turn out to be very different from what you've expected?

JW: Oh yes, completely. It’s impossible to get the right picture sometimes. You are running the video and just snapping in the dark with a hand held camera. Many times I leave in mistakes, which all contemporary artists do. Yes, you are always surprised when you get the film back, when something that you thought would really work didn’t. You might have an idea and you shoot all the photos and then when you put them together it just doesn’t work. But you just have to do it. But it is all thought up in the very beginning and what ends up is a variation of that original idea.

CM: How is it satisfying to you in a way that filmmaking isn’t?

JW: They are both satisfying in that they are both creative work. I don’t compare them; I don’t do them in the same place. I keep them very separate. Even though they both have humour. If you mean “satisfying” in terms of success, well, in the movie business I guess it would be how much the movie grosses, and in the art world it would be a sold out show. But the real thing you hope for in the movie business is a rave review from a critic you respect and the same thing in the art world. But both never really happen the way you want, in the same way they don’t make anything better. I learned a long time ago, with reviews you read the good ones twice and the bad ones once and then you put them away and never look at them again. But I do read them. I don’t believe anybody who says they don’t read them. But a lot of times in the artwork you do, the failure is better. Where in filmmaking, that doesn’t work. Well I guess you can have the failure of technique, but I just didn’t know any better. And the people who liked it would call it “raw” or “primitive” but that just meant “bad.” The same way in the art world when people use the word “rigorous.” It just means that other people can’t understand it.

I always thought movies are for the people and art is not for the people. Whenever they try to make art for the people it is a terrible idea.

CM: And that’s the inspiration for the piece Contemporary Art Hates You.

JW: It does hate some people. It hates the people who have contempt without investigation. People who say, “Aw, my kid could do that, that’s the most ridiculous thing.” It does hate them and it should hate them. And yes, those who do follow contemporary art and must learn the secret way to look at things, well, they're happy it hates those people. Because those people are too stupid to look.

CM: So contemporary art is not meant for widespread audiences.

JW: It could be if everyone would open up their mind enough and study enough and see enough so that they learn to see. Or learn to understand it. Or learn to be outraged by it. Which is what contemporary art is supposed to do in the first place—it’s suppose to wreck things, it’s suppose to destroy what came before. It’s suppose to alter what you think is good, I think. But unless you accept that and look for that or find delight or some kind of intellectual stimulation, it does hate you because you are stupid. And I don’t hate all stupid people, but I hate militantly stupid people.

TEXT BY CLAYTON MAXWELL

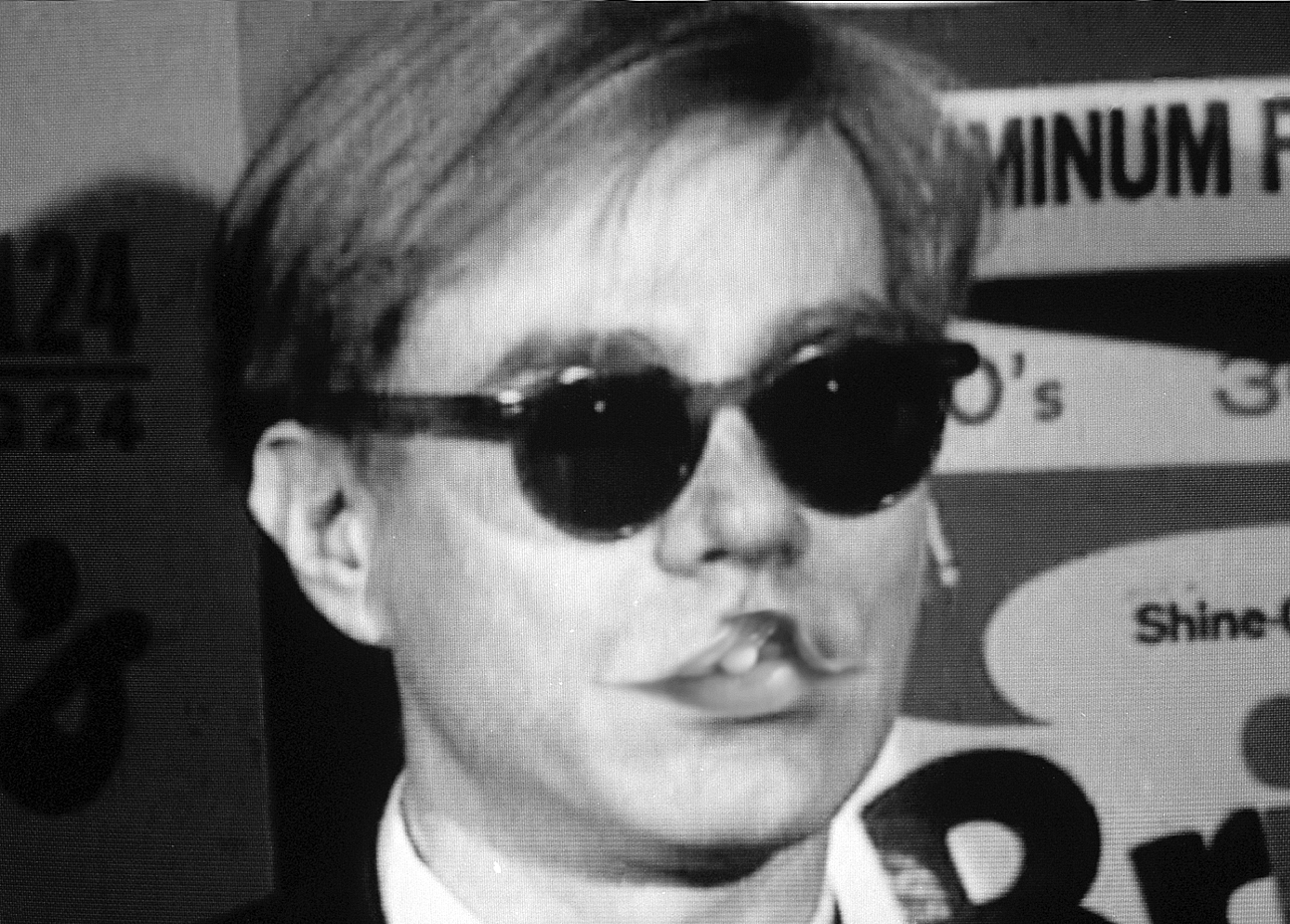

©picture John Waters

Detail from Hollywood Smile Train 2009, courtesy Gagosian Gallery