Salaryman

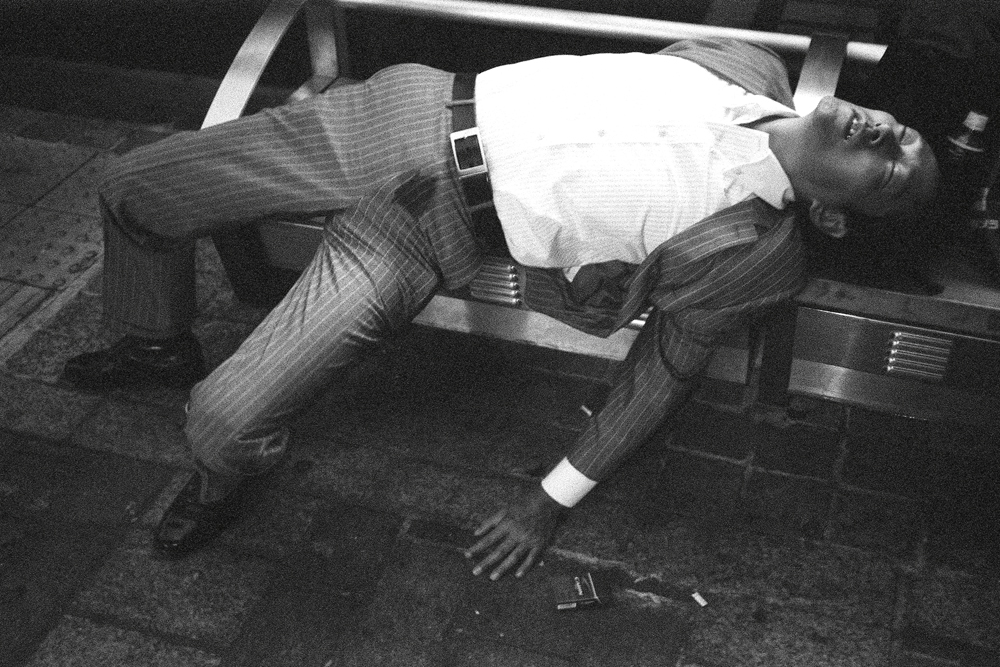

In the early morning hours in Tokyo, a contingent of young men turns up in the thousands on subways, buses and thoroughfares. Judging by their similar dress code (suit, tie, and briefcase) they resemble humanoid worker ants. However, 12 to 14 hours later the same young men take on a different appearance. They frequent bars in Tokyo’s Shimbashi district, karaoke establishments in Shinjuku, and smoke non-stop, while drinking too much sake and shochu. Later, lying supine or on their sides, unconscious with their mouths agape, their bodies appear on steps and sidewalks, or draped over waiting-room benches like living rags. These are not the casualties of a sleeping sickness that plagues the general public but rather “darkly celebrated” victims of modern life in Japan. When their faces happen to reflect consciousness at all, their dazed, watery-eyed stares are highlighted by perspiration and dribble. Such details accentuate Pawel Jaszczuk’s Salaryman—a black-and-white series by the Polish-born photographer working in Tokyo. The mix of culture, tradition and social habits exhibited in Salaryman culminates in a perplexing combination of actions. Jaszczuk’s images inform, irritate and amuse at the same time.

While Salaryman documents, as it were, the down side of the Asian work ethic, which boldly demonstrates social habits and economic patterns unlike those of its Western counterpart, in a less distinct voice this photo-series addresses the fear of not earning enough money to finance the so-called good life. Fundamentally, this fear lies at the heart of these unusual portraits of young Japanese men in states of abandon. Over the past decades, the same fear has driven an entire generation of young men into the grip of 12-hour-long workdays in Japanese firms and agencies, as if they plan to become millionaires before reaching the ripe old age of 30. Added to their voluntary or imposed ambitiousness, and encouraged by peers and employers in many cases, comes the self-effacing habit of drinking too much.

The suggested stress on earning, destructively attached to alcohol consumption, constitutes only one aspect of Jaszczuk’s series, which he developed as an art project focused on an antihero of sorts, a character as controversial as legendary in Japanese society. Content-wise at least two other aspects surface in these images of workaholics enjoying their curiously condoned, alcohol-ridden after hours. On the one hand, the viewer recognises a vague if persistent connection to surreal literature (especially books with nightlife themes), and an estranging reference to film noir on the other.

Jaszczuk’s unflattering shots of inebriated men sleeping off their drinking binges on streets and in public places in Tokyo (after missing their trains and buses home and drinking too much despite their well-known low resistance to alcoholic) suggest an eerie reversal of Yasunari Kawabata’s House of the Sleeping Beauties, the novel about a surreal brothel where male customers spend their time with unconscious women who remain “in a deathlike sleep” throughout the visit. Also, by virtue of the subjects’ poses and general aspect, Jaszczuk’s “male sleeping beauties” photographed dead drunk on street corners, subway platforms and at bus stops, suggest Weegee’s crime scene photography. Most significantly, these images make chilling and, at times, comical, references to “karōshi” or “death by overworking”.

Immediately following World War II the word “salaryman” became synonymous with the Japanese white-collar businessman, the ideal middle-class citizen, and the respected social climber. At that time the term frequently appeared in texts related to Japanese culture. Today such positive associations have vanished, and “salaryman” refers to a type of corporate existence in which drawing a salary perpetuates the day-to-day slavery suffered by office employees who lack the means (and sometimes the imagination) to escape their redundant existence. This results in the character previously held in esteem becoming more so an object of controlled pity (if not contempt) nowadays. Though candid and editorial on the surface, Jaszczuk’s images of men nose-diving into drunkenness are buoyed on the kind of questioning akin to artworks and not socially critical photo-essays. Accordingly, the photographer insists that Salaryman is neither judgmental nor critical. “My photography,” says Jaszczuk, “creates questions and not answers.”

As a graphic design student at the School of Visual Arts in Sydney, Australia, Jaszczuk first discovered his love of camerawork while attending a weekly photography course, and became a professional photographer after finishing his studies. In Tokyo, for the sake of placing his theme-oriented art projects, he works with an agency as well. But he would never refer to himself as a photojournalist or reporter. He produces editorial-like artworks, and his deep fascination with photographing unique people drew him to the salaryman as ideal subject matter. There was hardly a more absorbing and chameleonic character to photograph. As Jaszczuk remarks, “Photographing the salaryman means shooting someone who presents himself one way in the morning and another way at night.” As socially critical statements go, this is a far cry from a young Polish artist, born 1978, commenting on a public issue.

During the making of Salaryman, Jaszczuk showed the utmost respect for the privacy of his various “models”. Also, no one that he spent time with was ever photographed asleep in public. He guarded the identity of the men who generously shared their family problems with him, relating issues that evolved from heavy drinking and ranged from husbands accused of neglect to couples filing for divorce. These modern-day cases, which reiterate the salaryman’s existence in Japan since the middle of the 1940s, underscore how the term has always been used to express the merging of a social creature with a social phenomenon, while using the unmistakable image of a man devastated by the after-effects of working long hours, or better, the persistent image of a “work ethic” man, in suit and tie, striking the twisted pose of a fallen worker.

Jaszczuk, who claims to have neither judged the salaryman nor felt particularly inspired by other photographers as he worked, employs a decidedly present-day style for his series, and it functions without referencing any known schools of Japanese contemporary photography. Instead, while consciously ignoring Japan’s versatile world of fashion photography and the likes of Eikoh Hosoe’s poignant aesthetics, Jaszczuk’s series seems to hint at the troubling insights of Diane Arbus and the contortions of the models that appear in Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities series. If nothing else, the questions and suggestions brought to life in Salaryman speak for the breadth of Jaszczuk’s simple but enormously powerful photographs.

TEXT BY KARL E. JOHNSON

©image by Pawel Jaszczuk