In the year that saw the American satellite Explorer launch into orbit and the Russian Sputnik fall from it; Imre Nagy hanged for treason against Communism and Fidel Castro’s army galvanised for it, Jury Rupin took his first photograph.

Using a little-known bakelite model called a Smena, a low-cost 35 mm manufactured in the Soviet Union by LOMO, he snapped his grandmother feeding chickens in the yard of their house in Krasny Liman, a small town in the Donetsk region of the Ukraine, about 200 km from Kharkov. “When I was young” he would later recall “I never slept with the door closed. People just came and went. The house was heated with a traditional Russian wood-burning stove. They would put me into a barrel so they knew where I was, to stop me wandering off.”

For 40 years prior to his death in October last year, Rupin photographed the stuff from his day to day life. First an engineer, then a freelance news and feature photographer, his archive reveals an extraordinarily vivid portrait of Soviet history.

With five other photographers, including the illustrious Boris Mikhailov, he formed an experimental artistic collective called ‘Vremia’, or ‘Time’. For two years they succeeded in operating under the radar of the KGB, testing the limits of each others imagination: “We had a very lively exchange of ideas, almost to the point of fisticuffs. The neighbours once threatened to call the police because we were arguing so loudly!“ But good fortune was not to last. Their enforced disbandment, coupled with the ensuing harassment he suffered, goes some way to explaining why Rupin’s work has not until now been seen beyond the borders of the then USSR: “They stopped accepting packets from us at the post office when we were trying to send photographs abroad. They knew everything, they were watching me. My photographs were returned torn and defaced.”

He was born during what he gently termed “the hungry years.” 1946 saw severe drought for the Ukraine. Quite aside from the task of restoring order to the region after the devastation of the Second World War, they were forced to deliver a quota of 7.2 million tons of grain; estimates of the number of people who died range from 100,000 to upwards of one million. Exact figures are impossible because famine was not acknowledged by the Soviet regime; they would simply declare a census invalid if it showed a violent drop in population.

“We used to fry bread pancakes using fish oil,” Rupin told me. “My father couldn’t bear the smell; he used to have to leave the house when they were cooking. But I hadn’t known anything else so I enjoyed them. Maybe that’s why I survived.”

Rupin’s story is stitched inextricably to the story of the regime under which he lived. Each of his photographs conveys something of the ideologies the system propagated, or is a lyrical sabotaging of them.

These were years more “stick than carrot”, when the sophisticated instrument of the KGB warred against “harmful attitudes” and “hostile acts” via an intricate network of espionage. “For ordinary people who didn’t raise their heads above the parapet, who went about their ordinary business, attended all the meetings and demonstrations, things were okay” Rupin recognised. ”But it was bad for people like me; for artists, creative people who wanted to achieve something. The KGB were frightened we were going to destroy the Soviet societal structure.”

A contemporary article in Time magazine shows just how real the threat to dissenting intellectuals was: “Some are expelled, as outspoken Novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn was in 1974; others, like Nobel Peace Prizewinner Andrei Sakharov, are sent into internal exile; still others, like Sergei Batovrin, spokesman for an independent peace group, are shut away in psychiatric hospitals. Finally, there is the Gulag, which, according to human rights activists, holds some 1,000 known political prisoners today, though the count might be three times as large.”

Both Rupin and Mikhailov were regularly arrested and detained. They were always freed, but each arrest was scratched inkily against their names. Eventually the KGB used this record to have Mikhailov fired from his state-run employer. Because Rupin was freelance, he continued to find work, but “they wouldn’t leave my wife’s parents in peace: always questioning them: what was I doing, always trying to get them to persuade me to stop.”

As always, censorship proved to be the crucible in which artists like Rupin thrived: “The Soviet time enabled an opposition to develop. That was its biggest advantage. At its peak there were photographers and artists who existed only because they were opposed to official art.”

Rupin learnt his craft during his last year of military service. His parents sent him the money for a Zenit 3M, the first Soviet mirror camera with interchangeable lenses. “It was mostly taking pictures of the top brass, particularly one major who liked to have his portrait done, but I also had to cover the routine line-ups and parades.” That year Zenit had produced a line commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution. It seemed the Party would go to great lengths to ensure photographers remembered to capture appropriate material each time their shutter blinked.

By the time he left the army, his family had been moved to a three room flat on the other side of town, a down-at-heel area full of tall blocks. He escaped to technical college in nearby Slavyansk. “At school we’d had an excursion to the rail depot and I liked watching how they built engines, so decided to study mechanical engineering. My parents were shocked [his father taught Russian literature] but I went ahead and did it anyway. We were sent out on day release arrangements to factories. I worked on this huge piece of equipment that rolled out metal sheets into cylindrical shapes and then welded them to build enormous cisterns.”

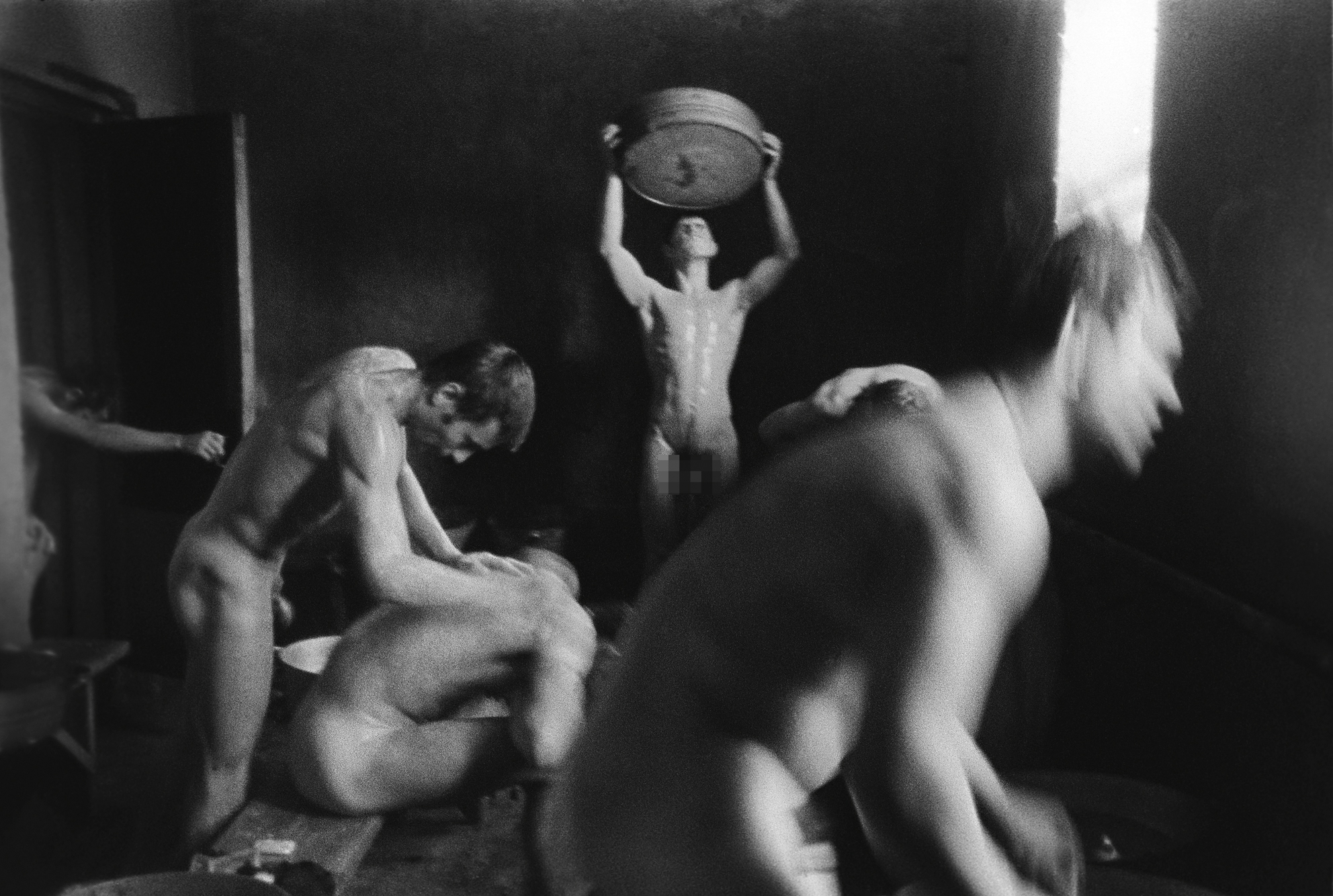

He continued to photograph. “At the end of my second year, I was sent to build cowsheds on a construction brigade [students were made to work during their vacations]. It was a tiny, remote village with one bath house.” He made a series of photographs of the men inside.

Oblivious to the camera, they seem engaged in a silent, private, elaborate dance. The sheen on their skin from the steam combined with the blur Rupin introduced by slowing his exposure turns them almost to clay. They could be figures on a Classical ceramic, but they are also at rest easily in the studies of bathers loved by Cezanne, an artist Rupin revered.

Unsurprisingly it was nude photography the KGB was particularly concerned about. “They used to call me in for little chats and tell me I should stop; that it wasn’t a proper thing for a Soviet man to be doing. So I tried to find ways of fooling them. I turned the bathhouse pictures into graphic works by solarising them until it seemed as if the subjects were not undressed.”

It was hard for Rupin to perfect this genre of photograph. “I didn’t have a proper studio of my own and I didn’t want to ask friends to lend me theirs, in case my work compromised them. So Boris and I took to photographing nude subjects outside, at night, where it was deserted.”

Gypsy Nude is one of these. “She was very brave; she took off her clothes for a photographer at a time when getting undressed for an artist was considered a bad thing. We went into the middle of nowhere and came up with this. I like it because it’s natural, alive. I prefer it to a set-up, studio nude.”

It was a picture of a naked woman on a town square at night that eventually closed the Vremia group. Rupin had sent the print to Poland for an exhibition, only to have it sent to the Polish KGB, and back to their Kharkov headquarters.

The exchange of ideas between Rupin and other photographers is fascinating, significantly so since they were often operating under the wire. Yaroslavl Tram Stop, with its red-coated trio picks up on Mikahilov’s Red Series. Both are playful, snapshot-style pictures which draw our attention to random, red objects, at the same time quietly suggesting years of Soviet history. ”That idea was in the air: red was everywhere. Boris and I just used to stroll around carrying our cameras.”

The two continued to work together after Vremia had disbanded, travelling to the south; the Baltic States; Moscow. On one expedition they met Vitas Lutskus. “He was the number one photographer in our eyes, his photographs astonished us. They were huge; nobody was producing work like that, 50 x 70, superb quality.” The three holidayed together in the Crimea, covering themselves in mud for a series of joyful photographs that are all the more poignant knowing Lutskus would throw himself out of a window not so long after.

Through working for Tass Ratu (Radio and Television Ukraine), the Krasnaya Znamya (Red Banner) newspaper and a publishing house called Prapor, Rupin travelled the length and breadth of the Ukraine oblast, recording a now defunct way of life.

The series Sorochincy Fair and November 7 are a precious example of his gift for reportage. In peppery shades of grey they log chance moments where posture, gesture and gaze crystallise into something astonishing. There is an incredible sense of time frozen in every stroke of his shutter. If you look at several of them one after the other, they mirror the elastic way we look around us. Pioneer looks rather more staged. “Such serious little faces, vowing to always be ready.” The movement was then at its height, boasting some 25 million members.

It is difficult not to call Rodchenko to mind. Like his predecessor, Rupin captures the vim of the Soviet ideal: the healthy body engaged in worthwhile pursuits–parades, fairs, pioneer groups. He has a superlative eye for peculiar distortions and is unafraid to use it–tilting his viewfinder, finding reflections, shadows. There is a real sense of his trying to find a means of understanding his world by trying it out from every angle.

Maya Mayatskaya, an animal trainer and Roitman the clown, are portraits from a series he shot of the Kharkov circus. At the time, the circus was seen on a par, even above, the ballet and opera: it was a truly egalitarian form of entertainment, enjoyed by all regardless of language or education. Rupin struck up a friendship with Roitman, who happened to be the Party Organiser and responsible for the moral conduct of every circus employee. “To convey this, I pictured him with a copy of Pravda on the table next to him.”

Rupin was proudest of his reportage. “If a photograph gets anywhere near showing life as it really is, that is the highest achievement. Photographs from 50 years ago, by Cartier Bresson, by Dorothea Lang; they are encyclopaedic-one photograph tells the whole story. Consider Lang’s White Angel Breadline. She’s snapped him with his back to the crowd, he’s standing like so. It’s fantastic because it shows everything that was happening in America at that time. It was the 30’s, there was hunger, unemployment and you can see it all in that picture.”

“Years ago I would have answered differently; I would have said my creative work meant more to me, because it took so much time and trouble to produce. At that time I wanted to engage in the process of photography. I sat there day after day with negatives. That was the interesting thing, the difficulty. That, and that like every photographer, I wanted to be different. But now I realise that the amount of work doesn’t necessarily dictate the value of a piece. To be honest the times when I took a camera with me and just photographed what I liked along the way, that really worked. Life is life, it’s what it is.”

TEXT BY LUCY DAVIES

©picture Jury Rupin, Sauna 1972