From Cairo where he was born, to Rio, Venice, Havana, and Paris, where he’s shot many of his selfportraits, Youssef Nabil has developed a body of work that speaks of themes seemingly well beyond his years. His images – filled with the pain of parting, nostalgia, solitude and death – hark back to a past epoch and art form, steeped in the dreamy romanticism of the long-lost art of classic Egyptian cinema of the 1940s and 50s.

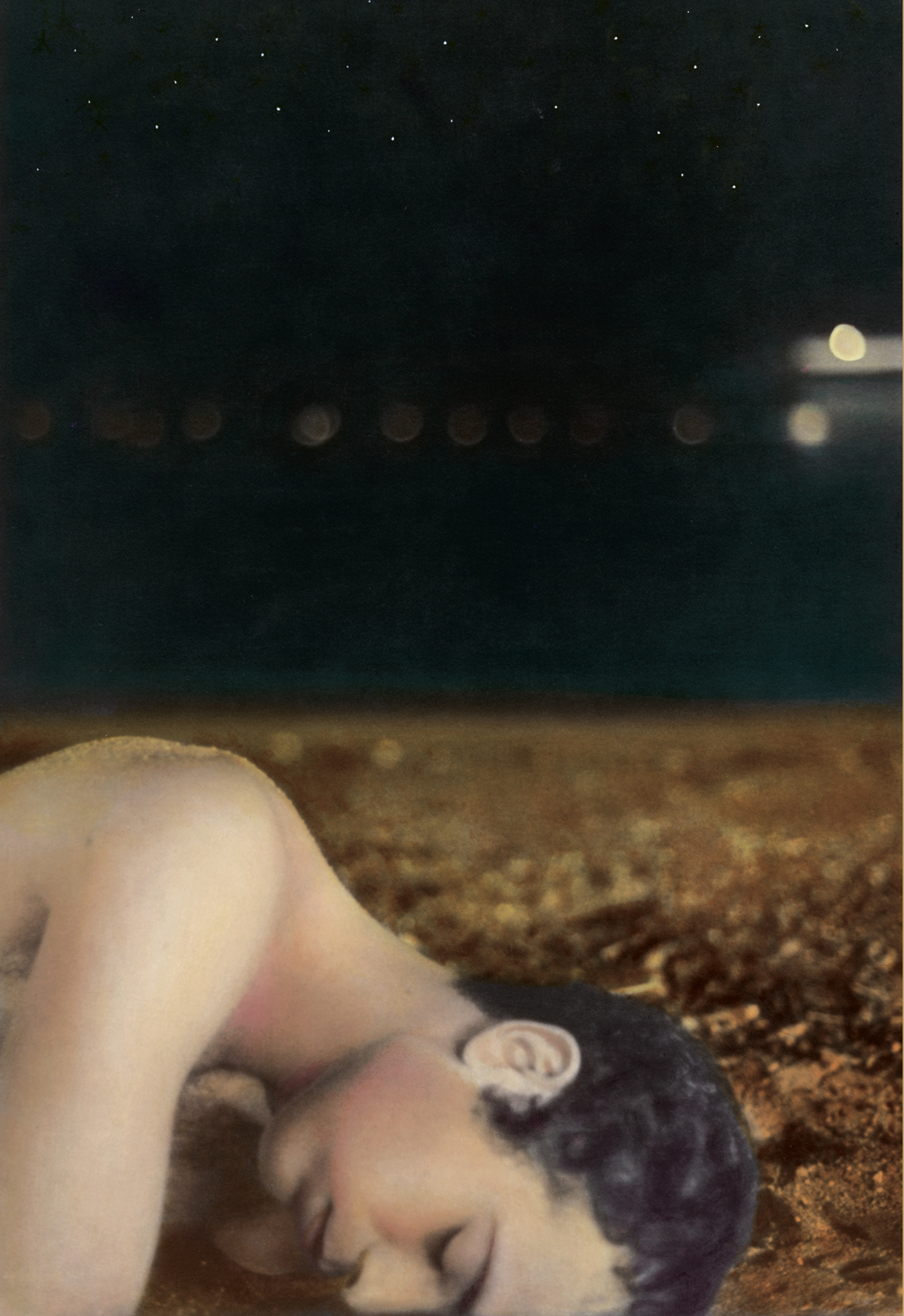

Nabil’s photography career began in 1992, when he met the late Egyptian-Armenian studio portrait artist Leon Boyadjian, widely known as Van Leo. The latter encouraged him to leave Egypt to seek inspiration and broaden his horizons. Between 1992 and 1998, Nabil learned the ropes as an assistant to fashion giants David LaChapelle in New York and MarioTestino in Paris. In 1999, he struck out on his own, doing editorial shots of Arab celebrities for Middle Eastern magazines. He also launched, in 2002, an ongoing project photographing women artists, including Nan Goldin, Tracey Emin and Louise Bourgeois. Recognition for his work quickly followed, with dozens of solo exhibitions worldwide, from Mexico City to Cape Town to Dubai. In 2003, he was awarded the Seydou Keita Prize for Portraiture at the African Biennial of Photography in Bamako. Nabil began the hand-painted self-portraits series, featured here, in 2003 while living in Paris, where he was invited by the French Ministry of Culture for an artist’s residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts. The series was displayed in Egypt for the first time in 2005 under the title Realities to Dreams. Nabil talked to Eyemazing about the emotions behind what he refers to as a “painted diary”.

Barbara Oudiz: There seem to be two almost opposite undercurrents in your self-portraits: on the one hand, a sense of optimistic yearning, a desire to go off in search of something that is perhaps just beyond the horizon, in photographs such as Looking out of the window, Sun in my eyes and I leave again. And at the

same time, there is a sort of pessimistic resignation, the suggestion that departing resembles death, as in My time to go and Hope to die in my sleep. Are these two emotions – yearning and resignation – in fact two ways of expressing the same sentiment?

Youssef Nabil: It is just the way I’ve always seen things; they go together like two faces of one coin. I think we always aim for something, we always want to reach or achieve something, but nothing is complete and nothing will stay the same. My self- portraits speak about my relation to my life and existence. I did them in different cities and each time I felt that I was just a visitor who would soon be leaving. My relation to my whole life is the same. For me, it is about coming to a place that is not yours then having to go.

BO: What does Realities to Dreams, the title you chose for the exhibition of your self-portraits held in 2005, evoke for you?

YN: I called the exhibition Realities to Dreams, because it is the way I always mix my dreams with my realities and my realities with my dreams. Life and death… Being with or away from the people I love is also the same for me. I think if you are a free spirit, all that doesn’t really matter.

BO: In what ways are your self-portraits inspired by the “golden age” of Egyptian cinema that thrived in Cairo some 60 to 70 years ago? Can the influence of this period and art form be felt in other projects of yours, or only in the self-portraits?

YN: All my work is somehow very connected. When I started my career I was very inspired by Egyptian cinema from the 40s and 50s that I used to watch a lot

on TV when I was a kid. I remember that I was always asking my mother about all the actors and where they were. Most of the time the answer was that they were all dead. I was in love with all these beautiful famous dead people. It did something to my subconscious and I wanted to meet the living ones. I wanted to photograph them, to have a part of them with me, keep them in my work, before they die or I die. My technique is also inspired by old Technicolor movies and old, hand-painted studio portraits. You can still feel all that in my other projects, including my self portraits.

BO: Can you tell us a little about your state of mind when you took them?

YN: The places I shot my self-portraits are places that I just happened to be visiting. Then I felt that at a specific moment I needed to make a self-portrait about a certain feeling I felt there. But I never really build them around a place; they are built more around a precise moment.

BO: You never make eye contact with the viewer in this series, indeed in many of your self-portraits your back is turned to the viewer. Why?

YN: When I photograph someone I become a sort of a voyeur, while in my self-portraits I let people watch me. I am an observer in these scenes, I’m very much aware of that, but also my self-portraits tell different stories, they are my most personal work. I never plan them really. Self-portraits come to me, I just feel that I need to say something at a certain moment and this is when I decide to do them.

BO: In your biography, it is said that Van Leo encouraged you to leave Egypt in the 1990s because he thought “photography as an art form was not sufficiently appreciated there.” Would you say that is still the case in Egypt today? If not, what has changed, and why?

YN: I think things will get better with time. It is difficult to be an artist in general, no matter what medium you are using. Van Leo was always telling me to go to the West, as he felt that my work would be more appreciated there. But things have changed since then in the Middle East in general, and there is a lot of interest right now in Middle Eastern contemporary art.

BO: You’ve been living in New York, I believe, since 2006. What does New York bring to your way of seeing or feeling compared to Paris, for example, or Cairo, or other cities?

YN: I’ve only lived in Paris and New York, and of course Cairo where I grew up. I have spent most of my life in Cairo. I only left five years ago; first to go to Paris, which I knew already from the time I was working with Mario Testino. I moved to New York two years ago, which I also knew from when I worked with David LaChapelle. I live in Harlem now. A lot of artists live around here. New York is the best place to be if you are an artist – though London and Berlin are good too. But Paris for me is the most beautiful city in the world.

TEXT BY BARBARA OUDIZ © picture: Youssef Nabil

Representing galleries: Michael Stevenson, Cape Town and The ThirdLine, Dubaï