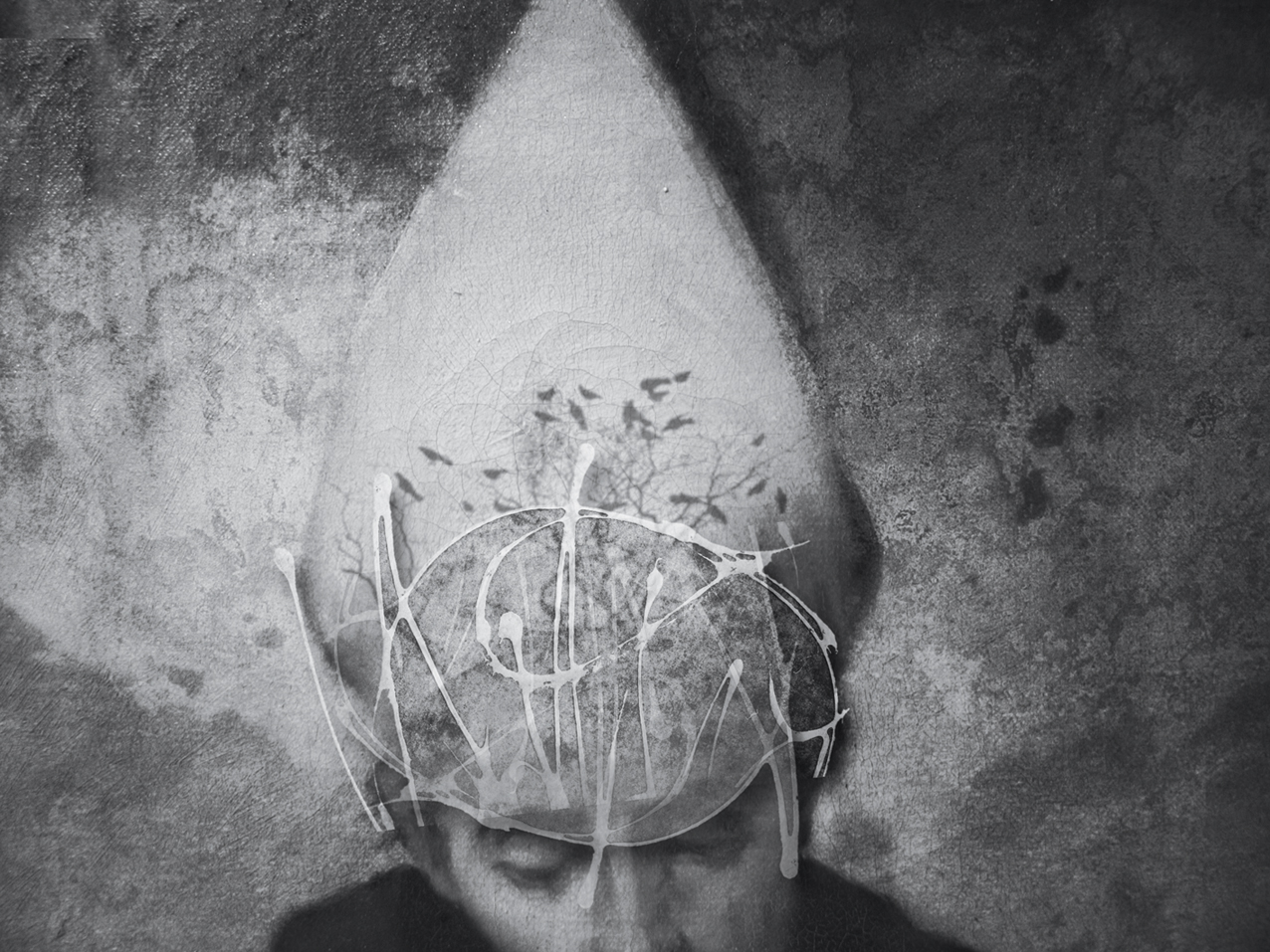

Art communicates truths or ideas that cannot be described by any other form of language. For this reason, the most stirring art can also be the hardest to write about. Germán Herrera’s work presents such a challenge. Herrera’s captivating photomontages unravel directly into the topography of the psyche. They strike personal notes, resonate deeply, and do not easily resolve into answers or translation. Herrera’s work is striking in how it immediately tugs at the mind on a subliminal level. Below the shadowy, luscious surfaces lurk ephemeral manifestations of philosophical concerns. Many of Herrera’s works seem to be palimpsests of unknown origin, teetering evocatively on the brink of obscurity.

Herrera exercises an alchemical imagination, sampling freely from classical painting, devotional iconography, and his own photographs taken from the natural world. Fragmented figures and ghost-like apparitions undermine the picture plane and connect to a dimension beyond the world of rational thought. He draws the material for his collages from a personal matrix of widely interconnected cultural influences, incorporating the traditions of his Mexican heritage, his studies of photography and neo-Reichian psychology, inspirations from art history, and his musings on the present.

Heather Snider: Your images have a rendering quality that is photographic but they are clearly not photographs by definition. Do you call your works photographs? What makes these works photographic? Is there a negative created in the process of making your work?

Germán Herrera: You are right in saying that they cannot really be labelled photographs. I consider them image based digital collages, which is more of a descriptive term for what I am doing. I have started to refer to the images as “endographs,” a term I have borrowed because, metaphorically, my imagery has to do with the inside. When asked what kind of photography I do I call it internal landscape or psychological landscape.

I am using the photographic platform because I was educated as a photographer. I studied photography, and loved Cartier-Bresson, street photography, the full frame, no editing, “Zen Archer” approach. And I still do go out and photograph, responding very intuitively to whatever I tune in to. But now I print from a file, I haven’t used film in a long time.

HS: Your use of digital technology is an important part of your work but not of your vision, in that the style of your work has a traditional, photographic feel, organic rather than synthetic. How important is technology to what you are doing, both technically and conceptually?

GH: Crucial, but I don’t think I have imposed decisions on my direction thematically or technologically. This work was enabled by digital possibilities and fuelled by my need to express. Suddenly I could weave a much more complex discourse than I could before. But it is my intention to accept reality as it is, not the way I would like it to be. I’ll explain: If I am limited by my camera, or by a certain paper, I will try to work within those constraints. Rather than limiting me this has opened up possibilities. If something is working, I don’t fix it. Digital output makes it possible to print photo-based images as “ink on paper” which has a resemblance to traditional processes like photogravure and photolithograph. I love how the image renders on cotton paper. I have enjoyed the use of technology but at the same time I am very conservative with it. I am slow to change things. Recently I’ve been thinking of printing smaller while technology increasingly makes it possible to print larger. I just like smaller prints.

HS: It appears that you access any pictorial vocabulary you feel drawn to: images you create yourself, images you find in books, in your environment. Are there some images you wouldn’t work with? What are the parameters you work with when pulling in visual content for your work?

GH: I would not use copyright protected images or the work of contemporary artists. This project, called A Book of Mirrors, has developed as a water stain would spread, from within, the parameter being defined by where the stain stops. I am watching it expand on its own. I think that if it is happening it is because there is an importance to it as a process and I do not impose limits on where it goes. Most of the images are not the product of an idea or concept that gets translated into a finished piece; they are more like the visual expression of an emotion. My intention is not to judge anything. When I recognise something emerging, I work with it, by concealing or revealing it. It feels like I am being guided through this process, like I am a vessel.

HS: There is strong tradition of Surrealism in Mexico, and the Surrealists worked in the philosophical terrain you are exploring. How do you think your upbringing in Mexico City might have manifested in your work?

GH: The production of the Surrealists has always been fascinating to me. Much of the cultural life of Mexico was influenced by the Surrealists, including the work of Alvarez Bravo amongst others. I was definitely aware of the Spanish heritage that came to Mexico City after the War. My grandfather was a hobbyist photographer, and he loved the work of a Spanish painter named Remedios Varo. I remember that she painted amazing, fantastical scenes with birds weaving starlight. My grandfather had books in his house of her work and he would take pictures of the details that he loved in her paintings and blow them up. His wife, Laura Cornejo, was an acquaintance of Tina Modotti and Edward Weston.

HS: There is also a sense of the devotional in your work. Folk-art milagros come to mind, and even alchemy. Can you talk about the mystic, spiritual quality in you work?

GH: I was brought up Catholic and definitely have a strong attraction to devotional imagery and Baroque art. I love the aesthetic sense with which figures are rendered in Catholic and Christian iconography. Devotional is a word I don’t use much because I associate it with organised religion. I am also drawn to the alchemists. In a way we are all seeking a connection to the divine within. I think this is the most basic drive of human existence, imbuing our lives with a sense of purpose. The tools we can use to achieve that: dreams, plants, intuition, meditation—I was interested in all of these before I realised I had something to say with my art.

HS: I am curious about your titles, which are mysterious and tend to loop the viewer back into a reconsideration of each image, but then don’t necessarily explain what you intend to reveal or express…

GH: I feel there is nothing casual about my titles. My intention is clear regarding what I want to say about a piece though it might be veiled. Generally I hint at a certain direction. For example, Don’t Follow the Wake is linked to a story I heard; there is no reason to spell it out. I know that the strength of what lives within the piece will reach some part of the viewer. I hope it makes a connection on an emotional level, providing an excuse to dream, for viewers to create their own stories, which are the ones they must pay attention to and decode, not mine. I sense that what I am doing is accessing material from the Collective Unconscious and the emotional connection is an intrinsic part of this process of recognition, turning the images into mirrors. The more individual the search the more universal it becomes. The phenomenon of life is like one big question mark that can’t be broken down into smaller parts; one just has to bow down to the experience of it.

TEXT BY: Heather Snider

Copy right pictures German Herrera